I did promise to share the resulting report with as little editing as possible and, though it’s a bit later than I said, I’m really happy to do that now.

If you’re not sure you quite fancy all 82 pages I’ve pulled out the highlights for you and you can read them below this blog. And for the super-quick read, here are the main outcomes and next steps:

– In January the Environment Agency met with the Dartington and it was agreed that everyone was both happy with the report and that assisted recovery was the right course going forwards (see ‘Conclusions’ in the highlights below for more on what this means).

– Dartington will commission a detailed implementation plan for the assisted recovery option to be ready, hopefully, by April.

– When we have a detailed implementation plan then work can commence from the spring. How quickly work will be completed is currently unknown. To begin with different aspects of the work will need to take place at different times so as to avoid negative impacts on fish and bird breeding season but also because, for example, trees are best planted in the autumn/winter.

– The other potential impact on the speed of implementation will be the available budget. The funds provided by the Environment Agency will not meet the total costs for this option which means it is down to Dartington to fundraise for the rest.

If we’re lucky we might be able to identify a large amount of funding to do the whole project this year. Alternatively we might have to split the plan into its different elements and look both for smaller amounts of funding for individual elements, consider what we can do ourselves perhaps with support from our conservation volunteers and also look out our delivery of the restoration might be done over several years.

Of course the preference is to do the whole project in one go so that, this time next year, we can all enjoy sitting on a bench on a boardwalk looking across the new pond and all the wildlife flourishing in it – but our main priority is not to let a lack of funds get in the way transforming Queen’s Marsh, even if it does take a little longer.

Lastly, as you can see in the report, the contributions of knowledge, reminiscences and images helped the team working on the feasibility study to build up a much fuller picture of what the marsh has been, what to look out for during any redevelopment process (such as the barges which may, or may not, remain under the grass), and how people would like to see the marsh used in future. So thank you very much to everyone who has been in touch about this project, we appreciate your input and hopefully there will be opportunities to get involved in the restoration itself.

Harriet Bell (previously food & farming manager at Dartington Hall)

Full highlights from the feasibility study report

Ecology

- A particularly pleasant surprise was that, despite years of attempted agricultural improvement (since approx. 1889), the soil samples show that the PH and nutrient levels of the soil are in fact good for many floodplain meadow species of plant. However, more tests on the stream itself, particularly the sediment, to look for contamination would still be beneficial. Thankfully Plymouth University are undertaking further work in this area as part of their separate research project. When it comes to the sward though the soil results mean ”there is significant scope to increase biodiversity on site”. (p15)

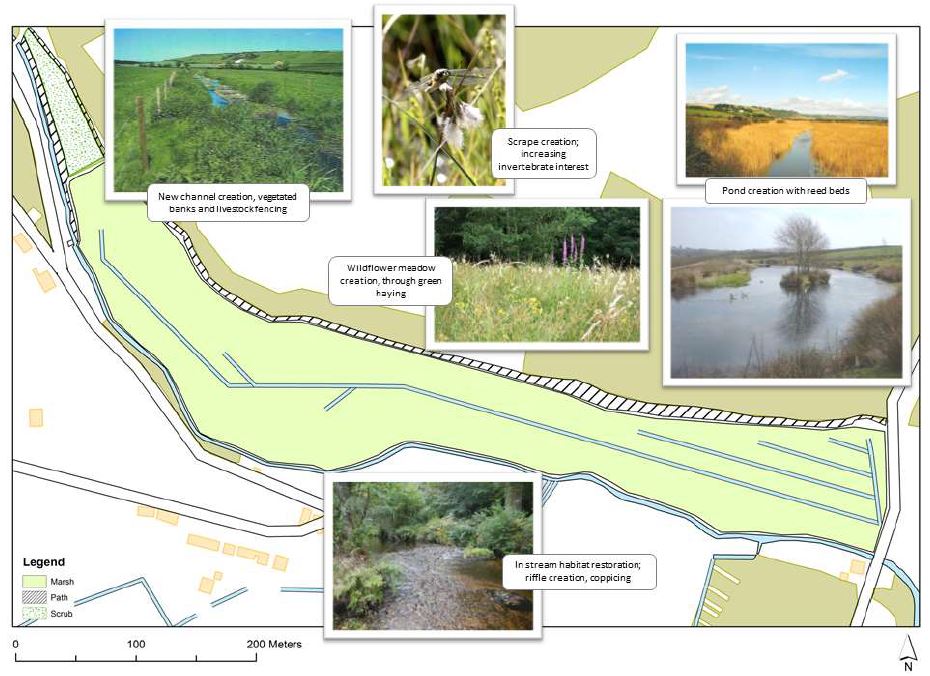

- Targeted enhancement would provide the most appropriate means of increasing biodiversity on site in the long-term. A range of different interventions would provide a mosaic of habitats across the site, allowing significantly greater structural and species diversity than currently exists. P34

- Habitat creation, which could include:

- Scrapes which are shallow depressions with gently sloping edges, which seasonally hold water generated by fluvial flooding and contributions from groundwater. They create obvious in-field wet features that are very attractive to wildlife.

- Wildflower Meadow areas. P35

- An area of deeper permanent water should be considered as this is likely to attract a range of bird species, and form habitat for invertebrates and foraging bats such as Daubenton’s and the rare barbastelle. p36

- Reed bed habitats p36

- Willow, alder and birch thrive in poorly drained, seasonally flooded areas/floodplains, growing together to make wet deciduous woodland. Wet woodland provides vital cover and breeding areas for mammals like otters, and also supports numerous bat species including pipistrelle, brown longeared and noctule bats.p37

- There are a range of ways restoration can be implemented for example with a larger budget wildflower plug plants can’t be brought to establish the new habitat quickly however, if the budget is limited spring hay from another field with better wildflowers can be cut and laid on Queen’s Marsh to transplant the seeds across. P35

- The generation of new habitats needs to be balanced against the function of Queen’s Marsh as a floodplain grazing field. P43

Flooding

- While fluvial flooding creates opportunities for habitat creation on the floodplain formed by the marsh, these opportunities must be balanced with other land use and management concerns. A key constraint, as reiterated by the Environment Agency in the course of enquiries made during this study, is that no work will be permitted that increases flood risk to property. These flood risk concerns extend to management of the river channel and banks for biodiversity gain in addition to re-engineering of the floodplain. P45

- Using data provided for and collected during this project, an effort was made to replicate and examine the existing flooding mechanisms from the Bidwell Brook. When it comes to concerns about flooding the evidence suggests the Bidwell Brook has limited impact in comparison with the River Dart which is the dominant influence. In fact the only property currently likely to be affected when the Bidwell Brook floods Queen’s Marsh, is the lodge house owned by Dartington Hall Trust at the entrance to the drive. Houses downstream are affected by the Dart. (p27-30)

- The report highlighted that if no intervention is made in Queen’s Marsh at all it is likely that the risk of flooding in the local area will increase. Work to restore the field to a wetland habitat may not have a significant impact on mitigating flooding in the region but it would prevent the risk of flooding from increasing. P63

Public engagement

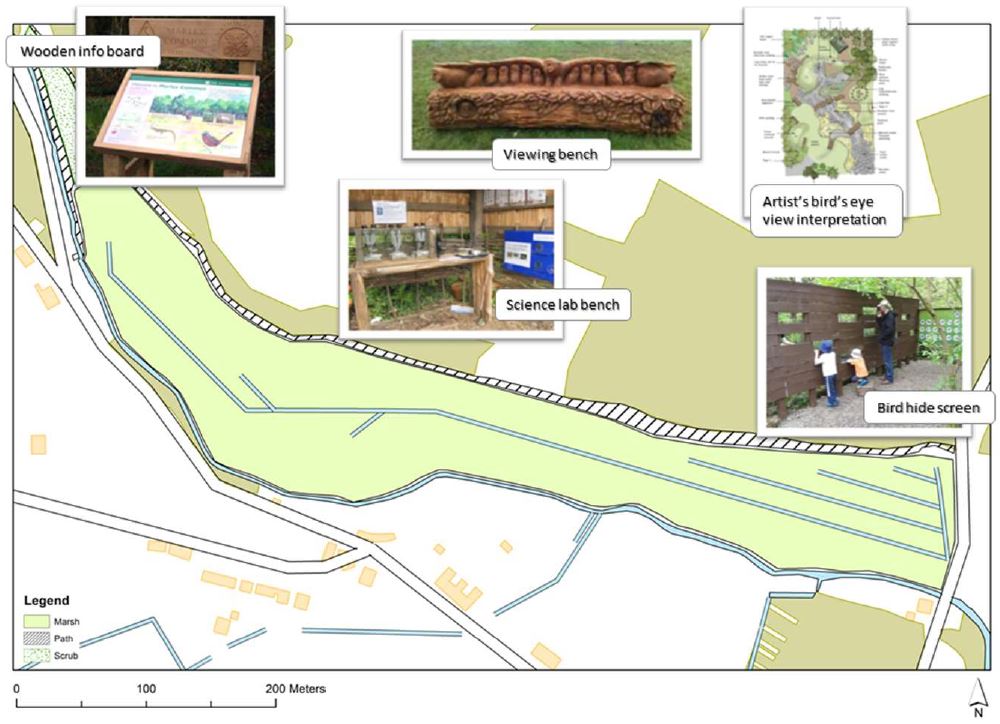

- “With Dartington estate open to the public and the Queen’s Marsh visual from a very active cycle path; enhancing the local public’s enjoyment and understanding of the restoration is vital to the success of the project. Signage boards, benches, bird hides could all provide opportunities to encourage public engagement with the site and educate visitors about the ecology of the landscape. P 47

- Signage creation could also create links to with the wider art community within Dartington and Totnes if that community was engaged in the design process p47

- It is possible that the Queen’s Marsh could be used for future public engagement events, such as education events relating to the habitats and wildlife on the site for both school children and adults, and community events that involve local artists or crafts. P47

Challenges and Constraints

- There are a wide range of potential ecological enhancements that could be implemented across the site. The final choice of measures is likely to be driven by budget, existing commitments relating to the agricultural management of the site and Natural England’s Higher Level Stewardship targets, and the geography and hydrology of the site, including soils, topography, water tables and flooding regime. All of these will affect the floral communities that are likely to establish successfully on the site and the subsequent management requirements of the habitats. P34

- A somewhat substantial limitation is the existence and location of several sewerage pipes in the field which will have to be worked around will act as a constraint to the amount of material that can be excavated above this structure. Particularly on the potential to create new channels so we need to look at how we might work with them or turn their locations to our advantage p 39

- South West Water helpfully engaged in dialogue around this project and has agreed that the new sewage pipe planned for this field will be made of ductile iron, which would make it less sensitive to landscape changes in the field. However, should any of the existing sewage pipe’s become exposed as a result of any planned landscaping there would be an additional cost to the project to make sure those pipes were protected.

- Irrespective of flooding from the brook, the large flux of water from the Dart in simulated and observed flood events is both an opportunity and potential constraint to what may be achievable.

- A more dynamic water management system than that currently in place may be required to balance any new drainage, pond and channel management requirements if this area is re-engineered – i.e. one which reacts to Dart and marsh water levels more actively than the passive arrangement of a weir and one-way gate by allowing unimpeded drainage through all three culverts where conditions on the Dart allow. P44

Conclusion

Preferred options

- Do nothing – This option would have to be considered if the cost:benefit ratio of other options on the site does not provide a favourable outcome or are prohibitively expensive. This option would leave natural process to achieve ‘restoration’ of the site and wetland features. This option would not allow maximum potential of the site for habitat and wildlife benefit. P48

- Functional-design – this would include establishing the Bidwell Brook in a new channel from the supposed palaeochannel and meandering through the middle of the marsh. However, there are several major constraints regarding this option such as the existing sewer pipes crossing the field. P48

- Assisted recovery – this would include habitat creation across the site in combination with enhancements to the existing brook. This option originally included consideration of a channel bifurcation, although this would need to be explored in more detail to assess hydrological and other constraints. This option could have several iterations. p 48

Assisted recovery was considered to be the most suitable option both for the site and funding requirements. The channel bifurcation element, however, was discounted as unlikely to provide value for money and there was concern about impacts upon the main channel. An assisted recovery design would include a cluster of scrapes, large permanent pond and semi-permanent pond fitted around the sewer pipes, areas of wildflower marsh, reed bed, woody debris and instream habitat, livestock fencing, wet woodland creation, and riparian corridor restoration p 49,50,51

A model of the ‘Assisted Recovery’ option was constructed to examine the viability of this design. Trial simulations were run to examine the impacts of a flood event from the Bidwell Brook (i.e. with the River Dart set to a steady state water level). Terrain modifications were arbitrarily defined for the purposes of illustration only. The results indicated no dis-benefit in terms of increased flood risk from this option. As should be expected, simulation of the flood recession illustrated the potential of the scrapes to hold water p56 &58

Costs are estimated in a region upwards of £60,000, with the creation of the large pond alone possibly costing around £40,000. Nor does that include some core costs, such as planning permission, or some desirable features such as bird hides p59

Dear Harriet. I am especially interested in the restoration of Queen’s Marsh to a wetland habitat. I have no specific skills as my background is in photographic and community education, co-establishing 3 social enterprise CIC’s in Plymouth. I am keen to learn new skills and participate in my other interest of conservation and this project seems to fulfil many aspirations. Hope to hear from you about any opportunities to become involved. Jon

Hi Jon and thanks for your interest in this project. If you would like to be involved then please do join our Conservation volunteer group. They do a tremendous amount of work across the estate, including on projects like this, and we truly depend on their passion, interest and commitment. Plus it sounds as though working with them would help you fulfil your desire to learn new skills. To get the ball rolling visit the volunteer page on this website and complete the Volunteer Interest Form or stop by the Volunteer Hub which is behind the Visitors Centre on the estate.

It would be helpful if you could include a diagram of where Queen’s Marsh is in relation to Totnes/Dartington/the estate. Some of us are not as familiar with the various parts of the estate as you are, and it would be lovely to know where exactly this fascinating project is!

Hi Jane, good point. We did provide a map on a previous story about Queen’s Marsh development – you can see that here. At some point, our hope is to have a more permanent home on the website for the Queen’s Marsh project which would include maps and much besides, but not just yet as the project is still at an early stage.

It will be exciting to see how this combines with the work being done in the opposite Berrymans marsh and how both can have a positive and developing impact on the flora, fauna and landscape of this lower section of Dartington for future generations! A very interesting proposal, it will be enriching to watch this take form and see the positive changes it will have on the wildlife of this area of Dartington and the river Dart. Hopefully it can go ahead soon and I look forward to when it does…

We often see habitats and biodiversity pressured and reduced by agriculture and increasing populations, I for one would like to applaud Dartington on its efforts to help support a greater biodiversity in restoring this area… Restoring being the operative word. The wetland will hopefully bring many more species a home and resting place and will be a joy for the local people. I can’t wait to see it develop and hopefully I will get to get my hands in the mud too. Nice work Dartington, and excellent work Harriet

I have watched the Queen’s Marsh cycle through the years and as your photos of the Canada Geese show, the area in question is functioning perfectly as it is. I would suggest that modifying this land in any way, shape or form to appease human perceptions of how Nature ‘should work’ are false and will produce a sad ecological travesty. Now that you have done a report and are aware of the wonderful gift of Nature you have, I strongly urge you to leave well enough alone and learn to enjoy the beauty of the marsh just as Nature intended. If you still feel the need to do some thing perhaps simply provide some historical information about how this marsh is evolving over time.

Hi Jonathan and thanks for taking the time to comment. I am however going to strongly disagree with your comment that our motivation is to “appease human perceptions of how nature ‘should work” which you believe will create a ‘sad ecological travesty’. Firstly, it’s a false statement that what you’ve been observing over recent years is natural – it isn’t – it’s Canada Geese making the most of a wet agricultural field. (The geese may be natural but the agricultural improvements haven’t been). It’s a landscape that was a great natural habitat which has been shaped and formed to its detriment by years of human intervention.

What we’ve been looking in to is how we might endeavour to repair some of that man-made impact, as detailed in the full report which is available at the top of this page. The sward was considered diverse in 1975; it’s now poor. In fact, the report states that, “Whilst the site is covered by a CWS designation, it is considered that the habitats present would not meet the current requirements for designation…It is considered that there is significant scope to increase biodiversity on the site through increasing species and structural diversity across the site and implementing an appropriate management regime.”

As you can read in Appendix 1 page 62/63 the option to do nothing was considered but there were constraints on that option such as “Fish passage to the upper catchment could be affected. Flooding over the causeway would be significantly exacerbated”.

What the report suggests is that, with the right interventions, the field might support more than Canada Geese, that with suitable habitat creation there may be longt-term benefits to waterfowl, invertebrates, fish, amphibians and potentially mammals such as otters.

In the last month we had some terrific news on the estate that a single change in management of the land had altered the habitat that land provided significantly enough that we welcomed back onto the estate a Red Status listed bird – that’s a bird which is globally threatened and has seen severe decline. Those are the species that can benefit from what we hope to do in Queen’s Marsh and, if we can manage it, will see that benefit, in a couple of years from now, because ten years from now it may well be too late for them.

I do understand why you might not be a fan of intervention that because it often doesn’t end well, but at least on this occasion it’s carefully considered and done with improvements that should benefit wildlife in mind.

I would prefer that Darlington funded this exciting project itself and didn’t resort to seeking funding from outside .

Hi Esther, thanks for your comment. So would we, but sadly we are currently running on a deficit which we are endeavouring to address through greater financial efficiency and consequently are only able to contribute a small amount ourselves to this project.

If your concern is that we might distract funders from addressing other causes, I can say that we will be primarily applying to funds which are specifically for supporting wildlife projects such as this one because potential partners believe them to be of value.

However, if we’re not successful in raising additional funds then we will endeavour to proceed ourselves without them – it just means that it will take many more years before we see a tangible impact.