Mary Bartlett came to Dartington in 1963 as a horticultural student. After her training she became responsible for the glasshouses, nursery and walled garden.

Mary Bartlett came to Dartington in 1963 as a horticultural student. After her training she became responsible for the glasshouses, nursery and walled garden.

She is the author of several books, including the monograph Gentians, and Inky Rags, a review of which can be found on the Dartington website. She is now the tutor for bookbinding in the Craft Education department. More blogs from Mary

We walked back from Chase Grove*, where we had scattered Cliff Harris’s ashes, among bluebells and wood ants nests under a canopy of the mature oak trees.

The first swallow darted overhead promising the first hint of summer. Rain later in the day washed the ashes into the soil.

Cliff had worked the land all his life and for much of it had been a forester in the Dartington woodlands, as his father had before him. He used to talk quietly about the wood ant colonies he found and the magnificent galleried mounds they build for themselves. He would bring his ferrets round to show our daughters and boxes of vegetables from his allotments for Christmas dinners.

He gently showed me how to plant bean seeds facing downwards to encourage the roots to go straight into the soil. In his retirement he worked with my late husband Bramwell, who was Estate Warden, planting oaks and protecting them with tree guards to safeguard the future of the woodlands.

The importance of the Dartington woods preoccupied Leonard Elmhirst when he and his wife Dorothy bought the estate in 1925. His moving recollections of the reconstruction of the Great Hall roof survive on tape. He spoke about the legacy of previous generations who had continuously replanted timber.

He described the selection and felling of the oak, how horses hauled it from the wider estate to the courtyard, and he recalled the recruitment of the last Arts and Crafts Movement architect (and the National Trust’s first) – William Weir – to replace the beams on the medieval walls using precarious wooden scaffolding. There is also a pictorial record showing how craftsmen shaped the timbers with hand tools – adzes, travishers and spoke shaves.

As the rebuilding continued, it became clear that the supply of ancient timber would soon be exhausted. Leonard sought advice approaching several bodies, including the recently established Forestry commission, whose new bosses turned out to be unkindly disposed towards private landowners. They told him they were much too busy with state business.

Undaunted, Leonard got in touch with W.E. Hiley, a lecturer in Forestry Economics at Oxford University. Hiley was soon to define forestry practices countrywide and such was his dominance that his influence is still visible in the English landscape. Hiley came to Dartington in 1932 and devoted the rest of his life to research at Dartington in the Woodlands Department. He wrote well, too, and his books are still much sought after. A Forestry Venture sets forth his own ‘Dartington experiment’ in exhaustive detail.

Documentation in the Dartington Archives, now kept at the Devon Record Office at Exeter, makes the impact of two World Wars on British woodlands all too plain. The best analyst of all that assiduously kept paperwork was Victory Bonham Carter, who gives one of the best accounts of the need for timber and wider implications for forestry after WW1in The Survival of the British Countryside.

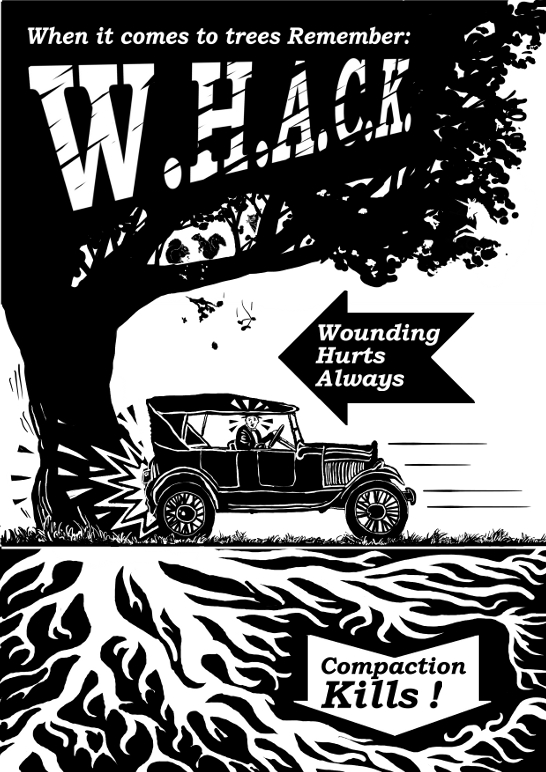

They might look indestructible (unless there’s a hurricane blowing), but trees are always fragile organisms and their cambium layer (the bark) is all too easily damaged. As a reminder, I not long ago printed a mnemonic slogan on the backs of old Woodlands Department labels: ‘WHACK- wounds hurt always, compaction kills. It was a message invented partly with the ravages of the grey squirrel in mind. It was kindly reworked into a poster by Simon Barron.

Once, red squirrels were common in the Dartington Gardens and across the estate, now there’s only the grey. The grey squirrel’s teeth are as effective at bark ringing and maiming our native trees as any chain saw in a tropical forest. Cliff and Bram worked tirelessly to protect our trees against the grey squirrel and, in my own quiet way, try to do the same.

It can be an uphill struggle! Recently Virgin Money used the grey squirrel in an advertisement suggesting ‘nobody looks after your nuts quite like…’ I wrote to the company to complain, enclosing UK Government policy guidance on how to deal with the catastrophic damage the creatures do. The explanation?

“We love red squirrels too and do understand the impact the grey squirrel introduction has had on our native species. But the more drab grey squirrel colours were better suited to our transformation with red cloak and eye mask then the much prettier red squirrel.”

And so to close the circle… The site of the old Dartington Sawmill is being redeveloped and the field opposite is packed with houses. When the Sawmill closed in 1983 I bought the beautiful brass rulers the men once used to measure the timber. Every time I use them in the bindery I hear the echoes of those early Dartington years.

In 2003 I took the poet Alice Oswald to meet Cliff Harris. She wrote the poem Tree Ghosts as her tribute to him, his life and times. I measured Alice’s lines, hand set and printed them in the workshop on an 1898 Arab treadle press – almost horse-drawn!

Mary

Notes

Permission was granted by The Dartington Hall Trust to scatter the ashes.

Permission was granted by Alice Oswald to reproduce the hand set version of Tree Ghosts.

Further reference: Tape recordings available in the history section.

William Weir at Dartington Hall by Reginald Snell 1986: www.scottisharchitects.org.uk/architect_full.php?id=204049

A New Tree Biology by Alex Shigo 1989

The Body Language of Trees, Claus Matteck and Helge Breloer 1994.

*Please note that Chase Grove is not open to the public as it is preserved for wildlife.

Tree Ghosts, by Alice Oswald

(Click arrow in corner to enlarge)

Hello Mary

I would love to have a copy of this pamphlet but I’m not sure if there are any available.

As a hobby I publish beautifully printed, illustrated and bound editions of poetry myself.

With thanks and best wishes

Andrew

Dear Andrew,

many thanks. have replied to your web site.

Good wishes,

Mary

Hi Mary,

I was interested to read your article and your reference to Cliff Harris . I remember him as ‘trapper’ Harris when I worked for Dartington woodlands between 1961-1964, and the Grey squirrel problem even then.

At present I live on the island of Crete and one day hope to return to Dartington and especially its woodlands.

I would be keen to find the stump of a yew tree, that according to the foreman Jimmy Miller, had been cut down in North wood thirty years before (1932) with other woodland to make way for Douglas Fir. I had this log of yew cut into small planks at the mill at Mortenhampsted where we took timber. My Father was a cabinet maker and wood carver and on my return from Africa in 1987 he made a fitting sign for a cottage we lived in in Surrey that was already named Yew Tree Cottage, he also made several reproduction Coffin stools for my wife and I from this beautiful hard red wood.

I thought you might like this story and its long memories.

Kind regards Tony.

Dear Tony,

Thank you for this. Cliff was really special to us, he worked with my late husband Bramwell when he was Estate Warden. Jimmy Miller was always telling me stories. We tried to capture the men and the hard work in the woods in Tree Ghosts. My husband was also a furniture maker and we have a desk made from the church yard yew when a large branch came down.

If you come to Dartington do come and find me, I would be pleased to learn more stories.

Best wishes,

Mary

Dear Mary,

I would certainly like to meet you one day when we return to live in UK and to revisit old haunts. Thank you.

Kind regards

Tony Whateley.

Lovely, well written article, with some fascinating details. Would be interested to hear in future blogs additional information about the development/ history of the woodlands, especially Chasegrove.