It’s not because there hasn’t been much to say, as there has been plenty going on – anyone who has been on the estate can see things are changing. It’s heart-warming how many people have commented on their joy at seeing the Jersey cows and goats in the fields around the estate, I think the sheep at Yarner certainly made their presence felt on the number of occasions they slipped through gaps in the fencing, Ross has put down his kale crop in preparation for his flock, and The Living Projects have begun work in earnest on developments at Pond Field.

But what of the promised changes that currently can’t be seen?

To anyone familiar with the Land Use Review and the associated map you will be aware there is a large field – almost 50 acres – as Proposed Agroforestry.

This was one of the more unusual quirks of the tenancy for Old Parsonage Farm when we took it to the market – some potential tenants may even have found our commitment to it off-putting. Incorporating trees into your farming system is not cheap – you have to buy trees, guard them as infants against rabbits, squirrels and deer, potentially fence them and then there’s the labour of planting, pruning and harvesting.

For Old Parsonage farmer Jon Perkin, the priority is building up his milking herds and facilities to provide a more imminent cash flow and postponing tree planting for a few years. Farmers aren’t incentivised to adopt agroforestry – there is no financial support for it provided through the Countryside Stewardship scheme, and they can actually receive less financial support generally as a result of implementing agroforestry. Too many trees and the land is no longer viewed as being farmed, and a farmer’s Basic Payment Scheme is reduced.

For Estate Manager John Channon on the other hand, there is a wish to see agroforestry established quickly as part of the Land Use Review in action.

The compromise is that the estate will carry the cost of planting the trees initially, but that the farm tenant will manage them – and when they’re ready to be cropped, start to pay a higher rent to cover the initial planting costs, which the farm tenant should be able to afford from selling the crop. Exactly what the costs will be remain an unknown, as it needs to be decided what will be planted and whether it will be silvoarable or silvopastural.

So when all this is such a challenge, why have agroforestry at all?

Agroforestry is holistic farming or farming by an agroecological approach, and there should be many benefits.

But the benefits of an agro-ecological approach as enacted through agroforestry should be much greater than just having two or three crops where previously you only had one. Look at the natural world around you – where do you see in nature just one type of plant growing in huge quantities? Even in forests and prairies, it may be largely trees and grass – but there’ll be a huge diversity of those, and many other things besides, because living things all exist as part of a very complex system and have co-evolved to benefit each other.

So by creating a farming environment which brings back an enhanced element of that natural diversity, you should see a multiplicity of benefits such as:

An increase in biodiversity

Improvements to soil moisture retention

Reduction of heat stress on any grazing animals

Additional minerals and nutrients to browsing animals

Increased nitrogen in the soil

Reduction of soil erosion

All of which should benefit the farm more widely than just the tree crop. Visit The Agroforestry Research Trust’s website if you’d like to know a little more.

For Dartington this should also then become a valuable teaching resource, which goes back to our history of trying new approaches to farming so that the wider world may be able to benefit from our experience – whether a success or failure. The Dartington Hall Trust founder Leonard Elmhirst had a particular love of trees, epitomised in his employment of Wilfred Hiley, then lecturer in Forest Economics at the University of Oxford.

So that’s the why of agroforestry, and recently we’ve been working on the ‘how’. This is no simple process but I’ve done my best to sum up the work so far below – so if you’re interested, please read on…

Harriet Bell (previously food & farming manager at Dartington Hall)

Planning our agroforestry efforts

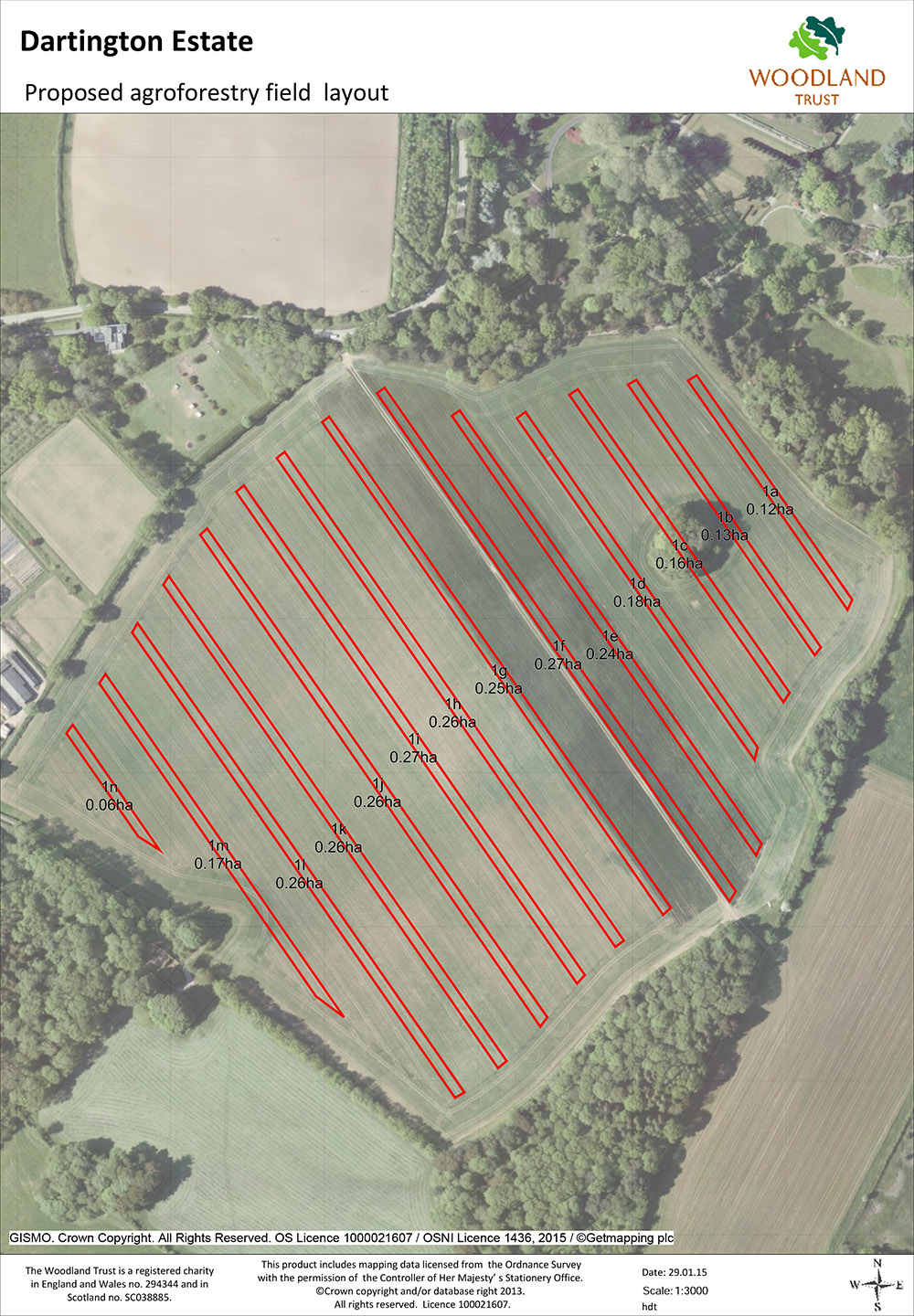

The starting point for advice and potentially funding was The Woodland Trust – they have already advised and funded some of the new trees being planted by Schumacher in their smaller agroforestry area and offer this support to farmers generally. Very helpfully, they visited the site and provided a proposed layout (see below) as well as details of funding options we may be able to utilise, though these would all be restricted to native British woodland trees and would not include any fruiting trees.

The next step was to gather together all the interested and knowledgeable parties on the estate who could provide context on what grows well locally, what trees the estate already has, what wood and produce the estate has an internal market for and what potential external markets there could be. We were particularly lucky to have the input of Martin Crawford, one of the UK’s leading experts on agroforestry, who runs a trial site of different tree varieties on the estate.

Things thought about and discussed included:

That native trees aren’t actually very good timber crops as they don’t tend to grow straight. Instead species such as cherry, sweet chestnut, sycamore, American black walnut, hybrid walnut (hybrids don’t produce nuts), European walnut (not straight growing but the bottom 3m grows straight, so has value) may be preferable.

There is little point in endeavouring to grow trees for nuts on the estate as the crops are generally devastated by squirrels which are prevalent.

A quick returning crop would be short rotation coppice which we could then use in the estate’s planned new biomass boiler.

We don’t necessarily need 6m wide tree strips, as suggested in the plan the Woodland Trust developed to help us get started. We could go as low as 2m, unless we’re growing fruit trees mixed with arable crops when you run the risk of damaging the trees with farm machinery if there’s not enough space around them. For the crop strips we probably actually want to grow strips wider than 30m, anywhere between 36 and 50m depending on the final height and spread of trees selected.

Regardless of what crop trees we plant, the system would benefit from inter-planting with nitrogen fixing trees – in particular Italian or American Red Alder.

Schumacher’s new Craft courses, such as The Craft of Woodworking, hope to make use of supplies from the estate. Fruits could be turned into jams and fruit leathers. Wood such as willow, hazel, cherry and ash can be used for activities such as weaving and furniture making.

Does agroforestry have to be trees? Could we plant shrubs such as Autumn Olive or Sea Buckthorn? What about hops to supply local breweries?

Is the answer all of the above? Divide the field into sections with different crops in different areas?

Effectively, a meeting which was supposed to help farmer Jon Perkin narrow down the options actually threw the gate open more widely. So what to do?

Well, now we know what we could grow we’ll be doing a little more thinking about what we can use and what we could sell and see if that helps us clarify things a bit more. Though I can say that based on the conversations I’ve had, hops will not be making the cut – sorry to disappoint all those beer drinkers out there.

Are the proposed field strips, as shown, possibly somewhat narrow – causing most of the land to be in shadow at times?

Harriet replies: Good question Sue. This is a first draft, not final plans. We are generally inclined to think the strips will be wider than as depicted here. The width will ultimately be determined by the crops as the final height of the intended trees obviously impacts the length of the shadows they will cast and then one also factors in what is being planted between the trees and how much sun or shade that crop requires.

The other factor incorporated into the planning will be the direction the strips go in, as that also impacts the degree of shade. Generally when growing crops in strips you plant them north to south to maximise the available light (as the sun travel east to west). However, with this field we’re also taking into consideration that it might benefit from contour planting, which is planting across a slope to create a water break which helps maintain top soil by reducing soil erosion, and we’re looking at practical details such as the most efficient access routes for machinery to gather crops from the trees and to plough or harvest the field strips. As you may have gathered from the blog we’re seeking a lot of expert input on the design (though the experts don’t always agree!) and it’s not any easy puzzle to put together but an interesting and enjoyable one, we’ll keep you updated on how we progress.