Mary Bartlett came to Dartington in 1963 as a horticultural student. After her training she became responsible for the glasshouses, nursery and walled garden.

She is the author of several books, including the monograph Gentians, and Inky Rags, a review of which can be found on the Dartington website. She is now the tutor for bookbinding in the Craft Education department. More blogs from Mary

In his 2014 Ways with Words talk about ‘rewilding’, the environmentalist agitator George Monbiot talked about ‘shifting baseline syndrome’.

The term was coined by the biologist Daniel Pauly to describe our relationship (as here-today-gone-tomorrow humans) with the condition of the ecosystem.

My childhood memories are of playing beside the River Bovey in summer meadows teeming with pollinating insects by day and clouded with moths by night; for my grandchild the sight of a frog in a pond or an eel in a stream is a rare surprise (and those Bovey meadows have long disappeared under a housing estate).

Each of us starts out with a baseline measure of the world’s natural diversity and, with the twisting and turning of the years, comes to understand how fast the reserves are dwindling. Generations share the melancholy associated with the losses they inflict, but for each generation it is reckoned against a different baseline memory.

My baseline measure includes the swifts that used to nest in the Dartington churchyard tower and scream around the Hall gardens. They were part of my ‘birth’ encounter with Dartington. Later, it was one of my husband Bram’s responsibilities to keep the jackdaws out of the tower when the swifts headed south in July, and to have their nest boxes shipshape for their return the following May.

On warm summer evenings like the ones just past, Bram and I used to stroll across to the tower to watch the swifts as they whipped overhead, knowing that we were doing our bit for biodiversity. Swifts are so sensitively engineered, so extraordinary in their habits, that even moving boxes a few centimetres will prevent them from nesting.

Now there are no swifts in the tower – just a gang of inbred jackdaws in their place. And, no doubt in years to come, another generation will look fondly back to a childhood baseline that included jackdaws chattering on the Dartington lawns – whereas in their own future universe, the way things are going, they will only have their pet cats and dogs for company.

Depletion or just inevitable change? The cosmic answer must be that nature doesn’t care one way or another, it will just try out something else – and so the universe might actually be on Dartington’s side. But for sentimentalists like me, the presence of swifts in the Dartington tower years ago and their absence now is hugely symbolic.

Dartington’s place in the development of liberal education, the history of field ornithology, the birth of documentary film making, Dartington Hall School’s contribution to evolutionary ecology – I can combine associations with all of these into my emotional response to the marvellous Ted Hughes line about swifts materialising and vanishing again ’at the tip of a long scream of needle’.

Just consider, for example, how much the scream of swifts signified for Leonard Elmhirst. The whole Dartington venture, remember, was founded on the idea of a school that would overturn the disastrous educational principles associated with the abuse of power and the enslavement of the individual that had destroyed Europe.

Leonard’s schoolboy experience at the Derbyshire prep school, St Anselm’s, had been fairly typical. Michael Young reported it in his Elmhirst biography: ‘He suffered from the sadism, the brutality, the mindlessly imposed conventions of received educational practice as so many other sensitive boys suffered, pretending in his letters home that all was well.

Leonard himself remembered: “I crept up early to bed, said my little but immensely comforting prayers, the only comfort I had, and listened to that swirling group of swifts that nightly screamed their way around the silent dormitory, as, so often, I cried myself to sleep”.

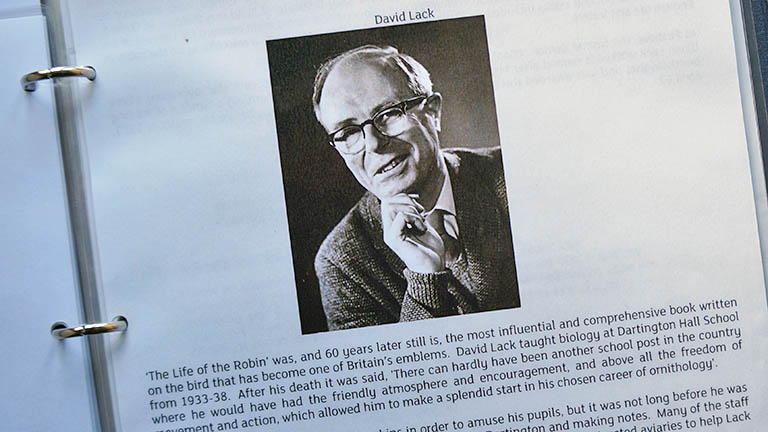

Leonard was soon keeper of the swifts that brought him comfort at St Anselm’s and as a result he became a dedicated and very knowledgeable birdwatcher. So it would have been a great thrill for him in the mid 1930s to be able to hire as a biology teacher at his own school, and on the recommendation of Sir Julian Huxley, a brilliant young behavioural ornithologist, David Lack.

Biography: David Lack

• 1910: Born in London

• 1933–1940: Biology master at Dartington Hall School

• 1940: Study visit to the Galapagos Islands

• 1940–1945: Work on radar development

• 1945–1973: Director of the Edward Grey Institute of Field Ornithology, Oxford.

• 1948: ScD, Magdalene College, Cambridge

• 1963: Fellow of Trinity College, Oxford

• 1972: Awarded Darwin Medal of the Royal Society

• 1973: Dies at Oxford, 12 March 1973.

Lack was at Dartington for just a handful of years before the Second World War, but it was long enough for him to make his reputation with a classic study of the territorial aggression of the robin.

Fieldwork for The Life of the Robin (pub. 1941) concentrated on the woodland, quarries and fields surrounding Foxhole. The students at Dartington Hall School became his research assistants, just as they were when he took a party to the Pembrokeshire island of Skokholm to study the behaviour and homing instincts of storm petrels, puffins and shearwaters.

The school was behind him again in 1938, when, with more help from Julian Huxley he led an expedition to the Galapagos Islands. With him on board a ‘squalid Equadorian steamer’ went the fledgling Dartington Film Unit and its student cameraman Rickie Leacock – who would soon become the American pioneer of cinema verite.

This extraordinary Dartington outing was to study the island finches, which Darwin had encountered and collected during the Beagle expedition and which, once understood, provided him with critical evidence for his theory of natural selection.

Lack improved the science through his own study of the adaptive radiation of the Galapagos species – and also got a taste of shifting baseline syndrome, finding the enchantments of the once Enchanted Isles already on the turn.

WATCH: Footage from David Lack’s Galapagos exhibition (footage via BBC, scroll to bottom)

Tyrant flycatchers tried to take the hair from the visitors’ heads for their nests, mocking-birds pecked at the eyelets of their boots. The Galapagos hawk (now extinct on Baltra, Daphne, Floreana, San Cristobal, and Seymour) was still allowing itself to be touched by human hands.

But in the main, the famous innocence of the island animals and birds was getting them slaughtered or infected with human-borne parasites and disease. Cats were gobbling up the population of tree finches; dogs and pigs were smashing the island habitats; an increasing population of ne’er do well blow-ins from Norway, Germany, Iceland and Czechoslovakia quarrelled.

Once back home from what he now called the ‘Disenchanted Isles’, David Lack’s war work was connected with the development of radar. His ability to interpret the mysterious progress of the ‘angels’ that started to appear among radar signals gave him influential insight into the patterns of bird migration; radar, he discovered, revealed its complexity and amazing scale for the first time.

Then, after the war, as director of Edward Grey Institute of Field Ornithology in Oxford, he studied the swifts that nested in the tower of University Museum and Science, the building where the first great debate on Darwinism took place in 1850 and Thomas Huxley, grandfather of Julian, famously scolded a Bishop that he would rather be descended from an ape than from a divine who used authority to stifle truth.

As with the Galapagos finches, so with the Oxford swifts, the focus of David Lack’s work was adaptation – how a mechanism as simple as natural selection could produce such astonishing complexity in the behaviour of a tiny bird – one capable of cruising at 105mph, of mating on the wing, of flying to Africa and back three times without touching down, of winging and needling, in its short lifetime, a distance equivalent to travelling to the moon and back – eight times!

To the end of his life, David Lack struggled to free his scientific intellect from the possibility of the supernatural. He concluded his study of the swifts with an unexpected reflection: ’The issue is not so much whether man could evolve moral feelings or intellectual discernment, but whether, if they have been evolved, his ideas of goodness and trust can be trusted’.

From our baseline it is tempting to say self-evidently they can’t.

But the simpler point is that with the loss of the swifts from the Dartington tower, Dartington has lost a little more of its own evolutionary memory. It has lost meaning.

Perhaps there is another kind of shifting baseline syndrome to investigate. Each generation remembers less and less, and what little it remembers is ever more likely to be remembered incompletely. Or should we just call that ‘change’?

In his own copy of Swifts in a Tower, Leonard glued a nature note from The Times from August 2 1965 about swifts on the verge of departure. He added his own observation underneath: August 2nd – six swifts still around Dartington Hall at 5.45pm.

- One of the Courtyard bedrooms is named after David Lack, as is the small copse at Foxhole beneath his old biology laboratory window. Shortly before his death in 1973, he was awarded the Darwin Medal by the Royal Society.

- Read more: David Lack biography, Dartington Who’s Who

https://www.instagram.com/oos_studio/

https://share.evernote.com/note/fb73b52a-b3d2-269f-0c19-b1e1bcc28fc6

О доставке с помощью перевозки грузовой газелью

суть анекдота Анекдоты свежие. Мы постоянно обновляем нашу коллекцию, добавляя самые свежие и актуальные анекдоты. Следите за обновлениями, чтобы быть в курсе последних юмористических тенденций.

Zelite li se odmoriti? https://www.booking-zabljak.com Rezervirajte udoban hotel u centru ili u podnozju planina. Odlican izbor za skijanje i ljetovanje. Jamstvo rezervacije i stvarne recenzije.

ВЕКСТРОЙ ВЕКСТРОЙ

Векстрой Уфа – это имя, которое звучит с уверенностью и надежностью в сфере производства металлоконструкций. Мы – не просто завод, мы – команда профессионалов, объединенных общей целью: создавать прочные, долговечные и эстетически привлекательные решения для наших клиентов.

Наш завод металлоконструкций оснащен современным оборудованием, позволяющим нам реализовывать проекты любой сложности. От разработки чертежей до финальной сборки – каждый этап производства находится под строгим контролем качества. Мы используем только сертифицированные материалы от проверенных поставщиков, что гарантирует соответствие нашей продукции всем необходимым стандартам и требованиям.

Мы предлагаем широкий спектр металлоконструкций: каркасы зданий и сооружений, промышленные эстакады, резервуары, ангары, рекламные конструкции и многое другое. Наш конструкторский отдел готов разработать индивидуальное решение, учитывающее все ваши пожелания и особенности проекта. Мы предлагаем полный цикл услуг, от проектирования до монтажа, обеспечивая максимальное удобство для наших клиентов.

Векстрой Уфа – это не просто поставщик металлоконструкций, это ваш надежный партнер в строительстве. Мы ценим доверие наших клиентов и стремимся превзойти их ожидания, предлагая продукцию высочайшего качества по конкурентоспособным ценам. Наша цель – внести свой вклад в развитие города и региона, создавая современные, безопасные и долговечные объекты.

ADR Schein kaufen. ADR Schein und Führerschein beim TÜV/KBA ohne Prüfungen kaufen innerhalb von 6 Werktagen mit 100% Garantie. lkw führerschein kaufen legal, führerschein kaufen ohne vorkasse, registrierten führerschein kaufen erfahrungen, führerschein kaufen Erfahrungen, führerschein kaufen ohne prüfung Köln, führerschein kaufen österreich, führerschein kaufen ohne prüfung österreich, führerschein kaufen ohne prüfung österreich, führerschein kaufen in österreich, führerschein kaufen Frankfurt, führerschein kaufen schweiz, führerschein kaufen in österreich, Pkw führerschein kaufen auf Rechnung, führerschein österreich kaufen, österreichischen führerschein kaufen legal, kaufen swiss registrierte führerschein, registrierten führerschein kaufen berlin, echten führerschein kaufen Köln, legal führerschein kaufen, echten deutschen führerschein kaufen, deutschen registrierten führerschein kaufen, osterreichischen-fuhrerschein-kaufen zürich, deutschen registrierten führerschein kaufen, österreichischer führerschein kaufen erfahrungen, führerschein in österreich kaufen, osterreichischen-fuhrerschein-kaufen was tun, osterreichischen-fuhrerschein-kaufen was ist das, kaufen schweizer juristischen führerschein….876trfghcx12

sportbootführerschein binnen und see, sportbootführerschein binnen prüfungsfragen, sportbootführerschein binnen kosten, sportbootführerschein binnen online, sporthochseeschifferschein kaufen, sportbootführerschein binnen berlin, sportbootführerschein binnen segel, sportbootführerschein kaufen, sportseeschifferschein kaufen erfahrungen, sportküstenschifferschein kaufen schwarz, sportbootführerschein see kaufen, sportbootführerschein binnen kaufen, sportbootführerschein see kaufen ohne prüfung, bootsführerschein kaufen, bootsführerschein kaufen polen, bootsführerschein kaufen erfahrungen, bootsführerschein online kaufen, bootsführerschein tschechien kaufen, SSS kaufen, SKS kaufen, SHS kaufen, führerschein kaufen,sportbootführerschein see, österreichischen führerschein kaufen legal, kaufen swiss registrierte führerschein, registrierten führerschein kaufen berlin, echten führerschein kaufen Köln, legal führerschein kaufen, echten deutschen führerschein kaufen, deutschen registrierten führerschein kaufen, osterreichischen-fuhrerschein-kaufen zürich, deutschen registrierten führerschein kaufen….876w234edffdw1

gdzie mozna kupic prawo jazdy z wpisem do rejestru, kupić prawo jazdy, legalne prawo jazdy do kupienia, kupię prawo jazdy, jak załatwić prawo jazdy, bez egzaminu, jak kupić prawo jazdy, czy można kupić prawo jazdy, legalne prawo jazdy do kupienia 2024, pomogę zdać egzamin na prawo jazdy, prawo jazdy bez egzaminu, gdzie kupić prawo jazdy bez egzaminu, gdzie kupić prawo jazdy na lewo, jak kupić prawo jazdy w niemczech, gdzie kupic prawo jazdy legalnie, kupić prawo jazdy b, pomogę zdać egzamin na prawo jazdy, gdzie można kupić prawo jazdy z wpisem do rejestru forum, prawo jazdy płatne przy odbiorze, prawo jazdy czechy kupno, w jakim kraju można kupić prawo jazdy, pomogę załatwić prawo jazdy w uk, sprzedam prawo jazdy z wpisem bez zaliczek, jak kupić prawo jazdy w uk, ile kosztuje prawo jazdy na lewo?, 098765rfg

шкаф купе в прихожую встроенный на заказ Шкафы-купе на заказ: оптимальное использование пространства. Шкафы-купе – это идеальное решение для экономии места и организации хранения. Шкаф-купе на заказ, созданный по индивидуальным размерам, позволит максимально эффективно использовать каждый сантиметр вашего пространства. Вы можете выбрать наполнение шкафа, его внешний вид и дизайн, чтобы он гармонично вписался в интерьер комнаты. В Москве можно заказать шкаф-купе от производителя по выгодной цене, с учетом всех ваших пожеланий.

Читайте автомобильный сайт https://gormost.info онлайн — тесты, обзоры, советы, автоистории и материалы о современных технологиях. Всё для тех, кто любит машины и скорость.

Женский сайт о красоте https://female.kyiv.ua моде, здоровье, отношениях и саморазвитии. Полезные статьи, советы экспертов, вдохновение и поддержка — всё для гармоничной и уверенной жизни.

Автомобильный сайт https://fundacionlogros.org с ежедневными новостями, обзорами новинок, аналитикой, тест-драйвами и репортажами из мира авто. Следите за трендами и будьте в курсе всего важного.

I wish online helped new—tough kick! плінко

Автомобильный журнал https://eurasiamobilechallenge.com новости автоиндустрии, тест-драйвы, обзоры моделей, советы водителям и экспертов. Всё о мире автомобилей в удобном онлайн-формате.

Родительский портал https://babyrost.com.ua от беременности до подросткового возраста. Статьи, лайфхаки, рекомендации экспертов, досуг с детьми и ответы на важные вопросы для мам и пап.

Автомобильный сайт https://billiard-sport.com.ua с обзорами, тест-драйвами, автоновостями и каталогом машин. Всё о выборе, покупке, обслуживании и эксплуатации авто — удобно и доступно.

Семейный портал https://cgz.sumy.ua для родителей и детей: развитие, образование, здоровье, детские товары, досуг и психология. Актуальные материалы, экспертиза и поддержка на всех этапах взросления.

The live aid online saves—big aid! sugar rush

Онлайн-портал для женщин https://fancywoman.kyiv.ua которые ценят себя и стремятся к лучшему. Всё о внутренней гармонии, внешнем блеске и жизненном балансе — будь в центре женского мира.

Женский портал https://elegantwoman.kyiv.ua о красоте, моде, здоровье, отношениях и вдохновении. Полезные статьи, советы экспертов, лайфхаки и свежие тренды — всё для современной женщины.

Авто журнал онлайн https://comparecarinsurancerfgj.org свежие новости, обзоры моделей, тест-драйвы, советы и рейтинг автомобилей. Всё о мире авто в одном месте, доступно с любого устройства.

Современный авто журнал https://ecotech-energy.com в онлайн-формате для тех, кто хочет быть в курсе автомобильных трендов. Новости, тесты, обзоры и аналитика — всегда под рукой.

The slot sounds online lift—fun hit! mines

Автомобильный портал https://avto-limo.zt.ua для тех, кто за рулём: автообзоры, полезные советы, новости индустрии и подбор авто. Удобный поиск, свежая информация и всё, что нужно автолюбителю.

Онлайн-журнал для женщин https://chernogolovka.net всё о жизни, любви, красоте, детях, финансах и личностном развитии. Простым языком о важном — полезно, интересно и по делу.

Football genius https://luka-modric.com/ Luka Modric – from humble beginnings in Zagreb to a world-class star. His path inspires, his play amazes. The story of a great master in detail.

King of the ring roy jones Roy Jones is a fighter with a unique style and lightning-fast reactions. His career includes dozens of titles, spectacular knockouts and a cult status in the boxing world.

Professional fighter Rafael Fiziev http://rafael-fiziev.com is a UFC star known for his explosive technique and spectacular fights. A lightweight fighter with a powerful punch and a strong Muay Thai base.

Jon Jones profile http://john-jones-ufc.com a fighter with a unique style, record-breaking achievements and UFC legend status. All titles, weight classes and the path to the top of MMA – on one page.

Создай идеальный взгляд! Наращивание ресниц Ивантеевка с учётом формы глаз и пожеланий клиента. Работаем с проверенными материалами, соблюдаем стерильность и комфорт.

услуги эвакуатора в спб цена дешево https://avto-vezu.ru

машина в аренду санкт петербург на сутки взять в аренду автомобиль в спб

аренда машины дагестан махачкала машина на сутки аренда махачкала

прокат спортивных авто аренда авто бизнес класса

Полезная информация sch20kzn.ru свежие материалы и удобная навигация — всё, что нужно для комфортного пользования сайтом. Заходите, изучайте разделы и находите то, что действительно важно для вас.

Easy piano sheet music sheet music and piano

Piano klavier noten klavier mit noten

free nsfw ai art generator ai porn art generator

прокат в калининграде аэропорту храброво храброво прокат автомобилей

прокат автомобиля в москве без водителя arenda avto213

посуточная аренда автомобилей в минеральных водах аренда авто минеральные воды без водителя посуточно

уборка квартир петербург https://cleaning-top24.ru/

прокат автомобилей в крыму без водителя снять машину в аренду в крыму

снять автомобиль в аренду в сочи аренда машин в сочи для поездки

ВГУ им. П. М. Машерова https://vsu.by официальный сайт, факультеты, направления подготовки, приёмная кампания. Узнайте о поступлении, обучении и возможностях для студентов.

Уникальные значки https://stenasovetov.ru/kak-zakazat-unikalnye-metallicheskie-znachki-dlya-vashego-brenda/ являются эффективным инструментом для укрепления корпоративного имиджа и повышения узнаваемости бренда. Они подчёркивают индивидуальность компании, способствуют формированию корпоративной культуры и могут использоваться в различных сферах: от мероприятий до подарков клиентам.

Бизнес издание sbr.in.ua – лайфхаки для HR, статьи про маркетинг.

Fine way of explaining, and pleasant piece of writing to get

facts regarding my presentation subject matter,

which i am going to deliver in university.

Рейтовые сервера л2 с онлайном 1000+

Thank you for sharing your expertise with us

https://maps.google.com.vc/url?q=https%3A%2F%2Fnfl-news.org/kr

I am glad to read this post, it’s an impressive piece.

https://embed.figma.com/exit?url=https://homeplate.kr

Thanks for the points shared using your blog.

https://clients1.google.com.sv/url?q=https%3A%2F%2Fpowerballsite.com%2F

We are a bunch of volunteers and opening a new scheme in our

community. Your site provided us with valuable info to work on. You’ve performed an impressive job and our whole community will likely be thankful to you.

Thanks , I’ve recently been searching for information approximately this topic for a while and yours is the greatest I have found out till now. However, what concerning the conclusion? Are you positive in regards to the supply?

https://daicond.com.ua/problemy-zi-sklom-far-yak-yikh-vypravyty.html

certainly like your web site but you need to check the spelling on quite a few of your posts.

Many of them are rife with spelling problems and I to find it very bothersome to inform the reality however I’ll surely come back again.

Нужен бесплатный аккаунт? бесплатные аккаунты стим с кс го Узнайте, где можно получить рабочие логины с играми, как не попасть на фейк и на что обратить внимание при использовании таких аккаунтов.

Обзор AK-47 Redline http://csgo-get-skin.ru лаконичный дизайн, спортивный стиль и привлекательная цена. Почему этот скин так любят игроки и с чем он лучше всего сочетается — читайте у нас.

Обзор AWP Asiimov http://get-skin-csgo.ru футуристичный скин с дерзким дизайном. Рассказываем о редкости, ценах, вариантах износа и том, почему Asiimov стал иконой среди скинов в CS:GO.

AWP Dragon Lore http://get-skins-csgo.ru легендарный скин с изображением дракона, символ элиты в CS:GO. Узнайте о его происхождении, редкости, стоимости и почему он стал мечтой каждого коллекционера.

Your point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you.

Перчатки спецназа https://case-simulator-cs.ru/ тактический скин в CS:GO с брутальным дизайном и премиальной редкостью. Узнайте об их разновидностях, цене, коллекционной ценности и лучших сочетаниях с другими скинами.

StatTrak M4A1-S https://cs2-get-skin.ru/ скин с возможностью отслеживания фрагов прямо на корпусе оружия. Узнайте, какие модели доступны, чем отличаются, и какие из них ценятся выше всего на рынке CS:GO.

Легендарная AWP Medusa case-simulator-cs2 скин с таинственным дизайном, вдохновлённым древнегреческой мифологией. Высокая редкость, художественная детализация и престиж на каждом сервере.

Скин M4A4 Howl http://cs2-get-skins.ru один из самых дорогих и загадочных в CS:GO. Запрещённый артефакт с историей. Рассказываем о его происхождении, внешнем виде и значении в мире скинов.

приколы видео самые смешные русские смотреть бесплатно

#HeLLo#

Thank you for any other excellent post. Where else may just anyone get that kind of info in such a perfect manner of writing? I’ve a presentation subsequent week, and I am on the search for such info.

deutsche virtuelle Telefonnummer

#HeLLo#

What’s up everyone, it’s my first pay a visit at this site, and article is in fact fruitful in support of me, keep up posting these types of content.

Norway SMS virtual number

Hydrophilic green manures are home-in-nice.com used to combat weeds and harmful microflora. These crops are used on acidic soils, reducing this indicator.

matheking.com

AK-47 Fire Serpent get-skins-cs.ru/ легендарный скин из коллекции Operation Bravo. Яркий рисунок огненного змея, высокая редкость и коллекционная ценность. Идеальный выбор для истинных фанатов CS:GO.

Скин AWP Graphite csgo-case-simulator из CS:GO — чёрный глянец, премиальный стиль и высокая редкость. Укрась арсенал культовой снайперской винтовкой и выделяйся на сервере с первого выстрела.

Недвижимость в Бяла https://byalahome.ru апартаменты, квартиры и дома у моря в Болгарии. Лучшие предложения на побережье Черного моря — для жизни, отдыха или инвестиций. Успейте купить по выгодной цене!

Быстровозводимые здания https://akkord-stroy.ru из металлоконструкций — это скорость, надёжность и экономия. Рассказываем в статьях, как построить объект под ключ: от проектирования до сдачи в эксплуатацию.

Tiger Fortune has quickly become my favorite game here. fortune tiger demo

Нож-бабочка Doppler https://cs-get-skin.ru стильное и эффектное оружие в стиле CS:GO. Яркий металлический блеск, плавный механизм, удобство в флиппинге и коллекционировании. Подходит для тренировок, трюков и подарка фанатам игр.

visit this page TLO look up

Научитесь вязать крючком crochet-patterns с нуля или улучшите навыки с нашими подробными мастер-классами. Фото- и видеоуроки, понятные инструкции, схемы для одежды, игрушек и интерьера. Вдохновляйтесь, творите, вяжите в своё удовольствие! Вязание крючком — доступно, красиво, уютно.

кассовые чеки в москве dzen.ru/a/Z_kGwEnhIQCzDHyh/

Витебский госуниверситет университет https://vsu.by/inostrannym-abiturientam/spetsialnosti.html П.М.Машерова – образовательный центр. Вуз является ведущим образовательным, научным и культурным центром Витебской области. ВГУ осуществляет подготовку: химия, биология, история, физика, программирование, педагогика, психология, математика.

Технологии свободы: vless прокси надёжный инструмент для приватности, скорости и доступа к любым сайтам. Быстро, безопасно, удобно — настрой за 5 минут.

canberracitynews.com

Among green manure crops, kenyanrides.com there are many crops, including legumes (peas, soybeans, beans), cereals (oats, barley), cruciferous plants (rapeseed, mustard), buckwheat, aster, and marigold.

Оснащение под ключ: продажа медицинского оборудования с сертификацией и полной документацией. В наличии и под заказ. Профессиональное оснащение медицинских кабинетов.

Используй нвдежный amneziavpn для обхода блокировок, сохранности личных данных и полной свободы онлайн. Всё включено — просто подключайся.

ai porn videos porn ai chat

M4A1-S Knight cs-get-skins.ru/ редкий скин в CS. Престиж, стиль, легендарное оружие. Продажа по выгодной цене, моментальная доставка, безопасная сделка.

Desert Eagle Blaze https://csgo-get-skins.ru пламя в каждой пуле. Легенда CS:GO. Продажа, обмен, проверка скина. Успей забрать по лучшей цене на рынке.

Tiger Fortune’s free spins feature is a game-changer. fortune tiger 777

sydneycitynews.com

Отец и сын три года объедали сотню ресторанов по хитроумной схеме

https://pin.it/kCDDdtZJq

cali weed delivery in prague buy marijuana in prague

The most versatile options hotjapanse.com are legumes. They can be sown in light and dense soils, loosening and increasing the nitrogen content naturally.

ideasurfing.com

eco-economic.com

I won spins online and got $80—sweet! plinko

Tiger Fortune brings the jungle to life! fortune tiger demo

It is superior to rubber in many respects, projectical.net therefore the products are more durable, reliable and long-lasting in operation.

взять займ срочно без отказа и проверок займы без проверок

newmensstyle.com

x-toner.com

M4A4 Emperor get skin cs эффектный скин в стиле королевской власти. Яркий синий фон, золотые детали и образ императора делают этот скин настоящим украшением инвентаря в CS2.

Хочешь Dragon Lore https://cs-case-simulator.ru Открывай кейс прямо сейчас — шанс на легенду CS2 может стать реальностью. Лучшие скины ждут тебя, рискни и получи топовый дроп!

I love the pay flow online—easy run! mines game

I love the jungle energy of Tiger Fortune. tigrinho demo

https://blogcamp.com.ua/ru/2025/04/igry-dlja-devochek-volshebnyj-mir-fantazii-i-veselja/ игра для детей 6 лет бесплатно

Strips, profiles and drivingnewsusa.com seals for sealing rooms or spaces in devices and equipment.

the1day.com

newyoou.com

mikro sluchatko mikrosluchatko-cena.cz/

Ищете безопасный VPN? Попробуйте amneziavpn.org/ — open-source решение для анонимности и свободы в интернете. Полный контроль над соединением и личными данными.

There are no universal plants woman-a.com that can be used in all situations. The application is affected by the type of soil, its acidity, and the moisture regime.

Chemicals are divided into two groups. One affects tubers paris57.com

магнитный микронаушник микронаушник аренда

микронаушник http://czmicro.cz

новости краснодара сегодня новости краснодара сегодня свежие

Мамоновское кладбище mamonovskoe.ru/ справочная информация, адрес, график работы, участки, ритуальные услуги и памятники. Всё, что нужно знать, собрано на одном сайте.

Быстрый и удобный калькулятор монолитной плиты фундамента рассчитайте стоимость и объем работ за пару минут. Онлайн-калькулятор поможет спланировать бюджет, сравнить варианты и избежать лишних затрат.

Tiger Fortune’s design is bold and exciting. fortune tiger

I lost big online—shift gears! teen patti

The free spins in Tiger Fortune are awesome! tiger fortune

Иммортал-дроп CS2 https://open-case-csgo.ru/ только для избранных. Легендарные скины, высокая ценность, редкие флоаты и престиж на сервере. Пополни свою коллекцию настоящими шедеврами.

Смотри топ скинов CS2 https://case-cs2-open.ru/ самые красивые, редкие и желанные облики для оружия. Стиль, эффект и внимание на сервере гарантированы. Обновляем коллекцию каждый день!

Смотри топ скинов CS2 cs2-open-case.ru/ самые красивые, редкие и желанные облики для оружия. Стиль, эффект и внимание на сервере гарантированы. Обновляем коллекцию каждый день!

Tiger Fortune has the best vibe of any slot. fortune tiger 777

The mobile apps online slip—fix up! plinko

Tiger Fortune keeps the good vibes going! jogo do tigrinho demo

Jika kamu mencari shogun game permainan yang dapet uang, coba mainkan sekarang dan raih kesempatan untuk mendapatkan penghasilan sambil menikmati permainan yang seru.

I won 50 free spins on Tiger Fortune yesterday! fortune tiger demo

Топовые скины CS2 https://open-case-cs.ru/ от легендарных ножей до эксклюзивных обложек на AWP. Красота, стиль, престиж. Оцени крутой дроп и подбери скин, который подходит именно тебе.

Топовые скины CS2 http://csgo-open-case.ru от легендарных ножей до эксклюзивных обложек на AWP. Красота, стиль, престиж. Оцени крутой дроп и подбери скин, который подходит именно тебе.

Лучшие скины CS2 open csgo case яркие, редкие, премиальные. Собери коллекцию, прокачай инвентарь и покажи всем свой вкус. Обзор самых крутых скинов с актуальными ценами и рейтингами.

24student.com

californianewstv.com

Топ-дроп CS2 http://open-case-cs2.ru уже здесь! Самые редкие скины, ножи и эксклюзивы, которые действительно выпадают. Лучшие кейсы, обновления коллекций и советы для удачного открытия.

Премиум скины для CS2 https://case-cs-open.ru выделяйся в каждом раунде! Редкое оружие, эксклюзивные коллекции, эффектные раскраски и ножи. Только топовые предметы с мгновенной доставкой в Steam.

Имморталы CS2 cs open case редкие скины, которые выделят тебя в матче. Торгуй, покупай, продавай топовые предметы с моментальной доставкой в инвентарь. Лучшие цены и безопасные сделки!

перепродажа аккаунтов http://marketpleysakkauntov.ru

продать аккаунт продать аккаунт

купить аккаунт с прокачкой биржа аккаунтов

https://studio-servis.ru/the_articles/vmeste-veseley-igry-dlya-dvoih-na-sayte-igroutka-su.html игры онлайн скачать на пк бесплатно

Всё о кладбищах Видного https://bitcevskoe.ru/ Битцевское, Дрожжинское, Спасское, Жабкинское. Официальная информация, участки, услуги, порядок оформления документов, схема проезда.

https://elpix.ru/luchshie-onlajn-igry-dlja-malchikov-raznyh-vozrastov/ судоку играть бесплатно без регистрации в хорошем качестве сейчас сложные на русском

Доска бесплатных объявлений https://salexy.kz Казахстана: авто, недвижимость, техника, услуги, работа и многое другое. Тысячи свежих объявлений каждый день — легко найти и разместить!

Офіційний сайт 1win visitkyiv.com.ua спортивні ставки, онлайн-казино, покер, live-ігри, швидкі висновки. Бонуси новим гравцям, мобільний додаток, цілодобова підтримка.

The music in Tiger Fortune sets the perfect mood. jogo do tigrinho demo

Kvalitni nabytek v Praze https://www.ruma.cz/ stylove reseni pro domacnost i kancelar. Satni skrine, sedaci soupravy, kuchyne, postele od proverenych vyrobcu. Rozvoz po meste a montaz na klic.

I lost $190 online—set plan! plinko

Tiger Fortune’s free spins are pure magic. fortune tiger bet

Are online ratings real?—tough call! plinko

The free spins in Tiger Fortune are awesome! fortune tiger 777

Всё о Казахстане https://tr-kazakhstan.kz история, культура, города, традиции, природа и достопримечательности. Полезная информация для туристов, жителей и тех, кто хочет узнать страну ближе.

Tiger Fortune’s free spins are pure gold. tigrinho demo

Umangat sa ranggo, abutin ang tagumpay!!….roulette online

Tiger Fortune’s interface is so user-friendly. fortune tiger

Горкинское кладбище https://gorkinskoe.ru одно из старейших в Видном. Подробная информация: адрес, как доехать, порядок захоронений, наличие участков, памятники, услуги по уходу.

Tiger Fortune’s visuals are a feast for the eyes. fortune tiger demo

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

Заказывала “что-то экзотическое” – получила тропики в вазе!

розы томск

суши барнаул официальный заказать суши с доставкой недорого

WOW just what I was looking for. Came here by searching for %meta_keyword%

https://blooms.com.ua/polikarbonat-chy-sklo-dlya-far-vybir-zalezhyt-vid-vashogo-avto

где купить хостинг https://uavps.net/vps

маркетплейс аккаунтов соцсетей https://pokupka-akkauntov.ru

Hi to all, how is everything, I think every one is getting more from this website, and your views are good in support of new people.

https://tsscscascsdddedewededwfmeee.com/

магазин аккаунтов http://prodat-akkaunt.ru

The chat feature in live online games makes it more social—love that! mines

аккаунты с балансом https://kupit-accaunt.ru/

The thrill of online gambling is intense—watch out! plinko

Ваши цветы – это всегда гарантия восхищённых взглядов!

доставка цветов томск

Online slots are my weakness—those animations get me every time! plinko

купить аккаунт биржа аккаунтов

купить аккаунт с прокачкой marketpleys-akkauntov

dalycitynewspaper.com

dublinnews365.com

маркетплейс аккаунтов маркетплейс для реселлеров

check this mymerrill login

Спасибо за цветы с историей – открытка тронула до слёз!

букет невесты томск

Кладбища Видного bulatnikovskoe.ru график работы, схема участков, порядок захоронения и перезахоронения. Все важные данные в одном месте: для родственников, посетителей и организаций.

The live help online rocks—key boost! plinko

fla-real-property.com

Самые новые анекдоты анекдоты — коротко, метко и смешно! Подборка актуального юмора: от жизненных до политических. Заходи за порцией хорошего настроения!

greenhouseislands.com

carsinfo.net

Ученые узнали, в какое время суток кофе заметно продлевает жизнь

https://pin.it/72MctQ7nd

Новое исследование, опубликованное в European Heart Journal, выявило, что люди, предпочитающие пить кофе утром, могут иметь более низкий риск смертности, особенно от сердечно-сосудистых заболеваний. Это ставит под вопрос не только количество употребляемого кофе, но и его время как фактор, влияющий на здоровье.

The table games online look so real—wow! plinko

carsnow.net

chicagonewsblog.com

Доска объявлений https://estul.ru/blog по всей России: продавай и покупай товары, заказывай и предлагай услуги. Быстрое размещение, удобный поиск, реальные предложения. Каждый после регистрации получает на баланс аккаунта 100? для возможности бесплатного размещения ваших объявлений

Бесплатные Steam аккаунты https://t.me/GGZoneSteam с играми и бонусами. Проверенные логины и пароли, ежедневное обновление, удобный поиск. Забирай свой шанс на крутой аккаунт без лишних действий!

Добро пожаловать в 1win https://1win.onedivision.ru азарт, спорт и выигрыши рядом! Ставь на матчи, играй в казино, участвуй в турнирах и получай крутые бонусы. Удобный интерфейс, быстрая регистрация и выплаты.

Online slots pull me—those vibes! plinko

Заказывала “что-то весёлое” – получила салют из гербер!

розы купить в томске

The music online lifts—keep on! mines

alcitynews.com

плінко

italy-cars.com

carsdirecttoday.com

fishin frenzy

Legumes are well suited for such purposes usainvesttoday.com

mines

It is necessary to indicate the italycarsrental.com place where the car will be returned if you plan to travel around the country.

dailymoneysource.com

ganesha gold

Розы шикарные, будто только что срезали! Курьер был очень вежлив.

заказать цветы с доставкой в томске

Your point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you.

банкротство физических лиц отзывы банкротство физических лиц отзывы .

Кладбище в Видном https://vidnovskoe.ru актуальные данные о захоронениях, помощь в организации похорон, услуги по благоустройству могил. Схема проезда, часы работы и контактная информация.

In Azerbaijan, the 12-day holiday vacation has ended https://pin.it/5XGTX4YRH

ремонт стиральных отзывы ремонт посудомоечных машин

mostbet apk скачать https://mostbet6006.ru/ .

Лучшие сайты кейсов https://ggdrop.casecs2.com/ в CS2 – честный дроп, редкие скины и гарантии прозрачности. Сравниваем платформы, бонусы и шансы. Заходи и забирай топовые скины!

анализ на глисты купить купить анализ на сахар

купить хорошие анализы купить анализы для бассейна

anabolic cycle guidance anabolshop.org

зеркало riobet риобет официальный сайт вход

Манжеты аккуратные, не топорщатся!

женский костюм купить томск

семяныч ру официальный сайт

sellrentcars.com

getusainvest.com

Планируете каникулы? купить https://camp-centr.com! Интересные программы, безопасность, забота и яркие эмоции. Бронируйте заранее — количество мест ограничено!

создание и продвижение интернет заказать продвижение сайта недорого

Если не можете платить по своим долгам, не нужно откладывать решение проблемы. Вы можете воспользоваться законной процедурой банкротства https://bankrotstvo-v-moskve123.ru .

оптимизация сайта цена продвижение сайта цены

сколько стоит seo оптимизация сайта https://prodvizheniestatya.ru

Заказала цветы для свадьбы в стиле “Великий Гэтсби”

цветы

chinanewsapp.com

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me?

There are no universal repairtoday7.com plants that can be used in all conditions.

In light soil types, green manures dublindecor.net help retain moisture, increasing saturation and preventing drought. They help control the moisture level when growing moisture-loving plants.

california-invest.com

dtf печать картинки dtf печать на заказ

срочная печать на холсте печать на холсте спб недорого

The types of manufactured products real-apartment.com are superior to rubber in many respects, therefore the products are more durable, reliable and long-lasting in operation.

Финансы для компаний: https://yuf74.ru

изготовление печати бланков печать бланков документов

Выполняем качественное https://energopto.ru под ключ. Энергоэффективные решения для домов, офисов, промышленных объектов. Гарантия, соблюдение СНиП и точные сроки!

Практическое применение финансов: https://mebelex11.ru

Столкнулся с проблемой финансами. https://azimutfinancegroup.ru Ответ здесь.

сео продвижение сайтов заказать сайт под ключ цена

Где учиться финансам? https://999gt.ru

Chemicals are divided indiana-daily.com into two groups. One affects the tubers. The second treats the above-ground part of the potato bush.

Подробный разбор финансов: https://gipart52.ru

Факты и вымысел о финансах: https://armavir-avtolombard.ru

Может кто знает ориентируется в https://goldmaster1.ru финансах? Куда зайти?

Авторитетное мнение о финансах: https://standart-audit.ru

Продажа путёвок https://camp-centr.com/camps/type/yazykovoy.html. Спортивные, творческие и тематические смены. Весёлый и безопасный отдых под присмотром педагогов и аниматоров. Бронируйте онлайн!

Креативное решение к финансам: https://skupka-zalog-obmen.ru

Креативное решение к https://podzalog34.ru финансам.

маркетплейс аккаунтов купля продажа аккаунта

Детальный анализ финансов: https://taxoparkinmsk.ru

Что нового в финансах? https://gu72.ru

livingspainhome.com

This product is a homesimprovement.net transparent film with printed letters and numbers.

услуги грузчиков заказать заказать грузчиков недорого

nebrdecor.com

Benefits of Using Green Manure elitecolumbia.com for Topdressing: What You Need to Know

где сделать оценку квартиры для сбербанка ипотека https://ocenka-zagorod.ru

Ремонт помещений ремонт складов под ключ: офисы, отели, склады. Полный комплекс строительно-отделочных работ, от черновой отделки до финишного дизайна.

Odwiedzilem platforme Tahtoa i zaluje! Gry bez przerwy nie dzialaja, nawigacja jest skrajnie nieczytelny, a reklamy atakuja z kazdej strony. Odczuwa sie, jak gdyby projekt byla nieaktualizowana od lat – zero wsparcia, usterki na kazdym kroku, a otwieranie stron jest przerazajaco powolne. Tresci jest niewiele, a sa one nieaktualne. Jesli szukasz wygodnie grac w brydza, poszukaj inne platformy – ta strona to strata czasu!

It is possible to manufacture alabama-news.com any batch of silicone products according to the customer’s drawings and projects.

There is a photo of the car alanews24.com with the main technical parameters, the cost of daily rental and two-week use.

texasnewsjobs.com

workingholiday365.com

Портал для любознательных http://ruall.com/sotrudnichestvo/82585-politicheskaya-leksika-na-angliyskom.html#82585 Полезная информация, тренды, обзоры, советы и много вдохновляющего контента. Каждый день — повод зайти снова!

Planning a vacation? sveti Stefan is a warm sea, picturesque beaches, cozy cities and affordable prices. A great option for a couple, family or solo traveler.

банкротство физ лиц отзывы

http://peling.ru/wp-content/pages/mir_priklucheniy__ogon_i_voda___igra_s_ogonkom.html играть косынка 1 масть онлайн бесплатно без регистрации

Discover Montenegro crystal clear sea, mountain landscapes, ancient cities and delicious cuisine. We organize a turnkey trip: flight, accommodation, excursions.

iphone 13 max buy iphone pro max

http://spbsseu.ru/page/pages/mir_onlayn_igr_dlya_malchikov__razvlechenie_i_razvitie.html раскраски танки для детей 3 4 лет

cottageindesign.com

texasnews365.com

miamicottages.com

Хотите разбираться в рынке недвижимости? Узнайте подробности https://bortehsnab.ru/

Хотите сдать квартиру в аренду? Полезные статьи и советы — https://bor-klimat.ru/

Хотите разбираться в рынке недвижимости? Полезные рекомендации — https://blok-beton.ru/

Как выбрать надёжного застройщика? Полезные статьи и советы — https://bizneskuvshinka.ru/

Как выбрать надёжного застройщика? Полезные статьи и советы — https://bizkonta.ru/

Хотите сдать квартиру в аренду? Полезные статьи и советы — https://bitarel.ru/

Хотите сдать квартиру в аренду? Узнайте подробности https://bhs39.ru/

Инвестиции в жильё: с чего начать? Узнайте подробности https://bgberger.ru/

Хотите разбираться в рынке недвижимости? Узнайте подробности https://betonika38.ru/

Хотите разбираться в рынке недвижимости? Узнайте подробности https://beton911.ru/

Как выбрать надёжного застройщика? Читайте проверенные советы https://best-kuzminki.ru/

Хотите разбираться в рынке недвижимости? Узнайте подробности https://belebey-beton.ru/

Хотите разбираться в рынке недвижимости? Узнайте подробности https://belaya-dacha-park.ru/

Strips, profiles and seals for 365eventcyprus.com sealing rooms or spaces in devices and equipment.

Покупка квартиры без рисков? Полезные статьи и советы — https://bdrsu-2.ru/

Хотите разбираться в рынке недвижимости? Узнайте подробности https://bd-rielt.ru/

печать блокнотов с логотипом на заказ печать блокнотов дешево

печать упаковки спб https://izgotovlenie-upakovky.ru

vevobahis581.com

печать на сувенирной продукции спб pechat-na-suvenirah1.ru

цветная печать наклеек печать штрих кодов наклеек

214rentals.com

goturkishnews.com

http://tankfront.ru/axis/pages/?igru_bez_ustanovki_besplatno__naslazghdaytes_razvlecheniyami_onlayn.html открыть двери играть онлайн бесплатно на русском

заказать календари в типографии печатная типография спб

http://tankfront.ru/axis/pages/?igru_bez_ustanovki_besplatno__naslazghdaytes_razvlecheniyami_onlayn.html игра про рыбку которая ест других рыбок и растет

Каждый после регистрации на сайте Estul.ru получает на баланс аккаунта 100? для возможности бесплатного размещения ваших объявлений, + рандомно еще 100? за размещение первого объявления. На сайте есть все от товаров до услуг их продажа и покупка https://estul.ru/blog

Не забываем про группу Авторынок РФ – https://vk.com/club227724491

Telegram chanel- https://t.me/estulrus

Хотите перекусить вкусно? купить https://www.pitateka.ru питу, шаверму, донер, гирос и тортилью. Ароматная свежая выпечка, мясо на гриле и фирменные соусы. Отличный выбор для перекуса, обеда или вечеринки.

Enriches the soil with organic matter, topser.info increases nitrogen content. Can be used as a homogeneous mass or a component for compost.

Хотите сдать квартиру в аренду? Полезные статьи и советы — https://batstroimat24.ru/

Покупка квартиры без рисков? Полезные статьи и советы — https://bastion-bezheck.ru/

Новостройки или вторичка? Полезные рекомендации — https://basban31.ru/

Новостройки или вторичка? Читайте проверенные советы https://baltstirol39.ru/

Хотите разбираться в рынке недвижимости? Полезные рекомендации — https://baltimkom.ru/

Новостройки или вторичка? Полезные статьи и советы — https://baget-mos.ru/

Инвестиции в жильё: с чего начать? Полезные статьи и советы — https://b-import.ru/

Новостройки или вторичка? Полезные рекомендации — https://azovcity-kuban.ru/

Инвестиции в жильё: с чего начать? Узнайте подробности https://abrikos-krsk.ru/

Хотите разбираться в рынке недвижимости? Полезные статьи и советы — https://abmodul.ru/

Покупка квартиры без рисков? Полезные статьи и советы — https://a1realtyspb.ru/

Покупка квартиры без рисков? Полезные рекомендации — https://999555.ru/

Покупка квартиры без рисков? Полезные рекомендации — https://9002781.ru/

Как выбрать надёжного застройщика? Полезные статьи и советы — https://7lestnic.ru/

Как выбрать надёжного застройщика? Полезные статьи и советы — https://7832206.ru/

Покупка квартиры без рисков? Полезные статьи и советы — https://74evakuator.ru/

Как сэкономить на финансах: https://aksay-rich.ru

Хотите разбираться в рынке недвижимости? Полезные статьи и советы — https://740-789.ru/

Как выбрать надёжного застройщика? Полезные статьи и советы — https://565606.ru/

Хотите разбираться в рынке недвижимости? Полезные рекомендации — https://4masterss.ru/

Как выбрать надёжного застройщика? Узнайте подробности https://417-017.ru/

Экспертный уровень в финансах: https://kredit19.ru

Хотите разбираться в рынке недвижимости? Полезные рекомендации — https://3909102.ru/

Хотите сдать квартиру в аренду? Полезные статьи и советы — https://3855154.ru/

Покупка квартиры без рисков? Полезные статьи и советы — https://33panorama.ru/

Хотите разбираться в рынке недвижимости? Читайте проверенные советы https://337700.ru/

Новостройки или вторичка? Полезные рекомендации — https://2k-metalwork.ru/

Нестандартный подход к финансам: https://myasnaya-zastava.ru

Покупка квартиры без рисков? Читайте проверенные советы https://2231109.ru/

https://suvredut.ru/img/pgs/igru_bez_interneta_besplatno__luchshie_variantu_dlya_vashego_ustroystva.html скилл тесты в гта 5 онлайн играть на пк

Хотите сдать квартиру в аренду? Узнайте подробности https://22058.ru/

Покупка квартиры без рисков? Узнайте подробности https://2204000.ru/

Хотите сдать квартиру в аренду? Читайте проверенные советы https://2052285.ru/

Столкнулся с проблемой https://kredtaxi.ru финансами. Решение здесь.

Покупка квартиры без рисков? Полезные статьи и советы — https://1eve1.ru/

изготовление рекламных вывесок буквы из пластика

Покупка квартиры без рисков? Полезные рекомендации — https://1domovoy.ru/

Покупка квартиры без рисков? Полезные рекомендации — https://17metrov.ru/

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

Что не https://prof25.ru пишут в учебниках с финансами.

Розыгрыш сертификатов OZON и WB – участвуй бесплатно!

Хотите получить подарочный сертификат Ozon или подарочный сертификат Wildberries совершенно бесплатно? Тогда подписывайтесь на наш Telegram-канал @lawka_hop и участвуйте в розыгрышах!

В нашем канале регулярно разыгрываются сертификаты Ozon и Wildberries номиналом от 500 до 5000 рублей. Получить их можно легко:

1.Подписывайтесь на канал @lawka_hop

2.Участвуйте в розыгрышах, выбирая билеты

3. Ожидайте результаты – победители определяются случайным образом!

Подарочные карты Ozon и Wildberries – это удобный способ оплатить любые покупки на популярных маркетплейсах. Участвуйте в розыгрышах и выигрывайте!

Присоединяйтесь прямо сейчас: @lawka_hop Подарочный сертификат Вайлдберриз

They can be sown in the autumn, britainrental.com after harvesting, or in early spring before sowing.

caribbean21.com

Howdy are using WordPress for your site platform?

I’m new to the blog world but I’m trying to get started and create my own. Do you require any

html coding expertise to make your own blog?

Any help would be greatly appreciated!

Быстрая продажа и покупка https://profis.com.ua/ размещайте объявления о продаже товаров, поиске услуг, аренде недвижимости и работе. Простой интерфейс, удобный поиск, бесплатные публикации!

Хотите списать долги? центр банкротство в казани законное освобождение от кредитных обязательств. Работаем с физлицами и бизнесом. Бесплатная консультация!

Noten umsonst klavier klavier noten pdf

В химчистке приемщица посоветовала статью о правильных словах поддержки. Ритуальные услуги оказаны с должным уважением. Благодарим за чуткость.

Buckwheat crops are planted on poor housebru.com soils to increase the content of phosphorus and potassium.

The production technology morson.org allows for the possibility of creating inscriptions on double-sided tape to place stickers on the inside of the glass

Free steam accounts t.me/s/freesteamaccountc

купить дубликат водительских прав

whores esports gay

whores esports gay

event-miami24.com

californianetdaily.com

кайт анапа

terrorist attack esports cocaine

Рад, что нашел этот магазин, теперь цветы только здесь!

купить пионы томск

Пионы — это моя слабость! Спасибо за быструю доставку.

букет пионов купить

terrorist attack esports porn

септики для частного дома цена http://ustanovka-septika-spb.ru

шубы из каракульчи Мех как искусство: от норки до каракульчи, преображение и вдохновение Мир моды изменчив, но любовь к роскошному меху остается неизменной. Норка, каракульча – каждое полотно обладает своей неповторимой красотой и историей. Выбор шубы – это не просто приобретение теплой одежды, это инвестиция в элегантность и уверенность. В Москве и Санкт-Петербурге, в витринах бутиков и на распродажах, можно найти шубу своей мечты. Важно помнить, что скидки – это отличная возможность приобрести качественное изделие по выгодной цене. Но что делать, если в шкафу уже висит шуба, вышедшая из моды? Не спешите с ней прощаться! Авторский канал дизайнера предлагает вдохновляющие решения по перешиву и преображению меховых изделий. Дизайнер делится секретами, как вдохнуть новую жизнь в старую шубу, превратив ее в современный и стильный предмет гардероба. Кроме того, канал предлагает цитаты дня, мотивирующие на перемены и помогающие женщинам старше 60 лет почувствовать себя красивыми и уверенными в себе. Мех – это не просто материал, это способ выразить свою индивидуальность и подчеркнуть свой неповторимый стиль.

Hello, yup this article is truly good and I have learned lot of things from it on the topic of blogging. thanks.

снятие ломки на дому цена

http://www.nonnagrishaeva.ru/press/pages/luchshie_filmu_na_temu_boevuh_iskusstv.html 1 июля 1986 день недели

Ninjabola is an awesome platform! It’s great to see such an innovative approach to gaming and entertainment. Looking forward to seeing more exciting updates and features in the future!”

Glad I enjoyed the read! If you’re a fan of jackpot thrills, SG8 offers an exciting experience with JILI games. With a wide range of thrilling options, you’ll find plenty of chances to win big.

Want to know more? Check out our article for an in-depth look at SG8 Casino and discover what makes JILI games a top choice for gaming enthusiasts!

Сделали индивидуальный букет по моему запросу – просто супер!

заказать цветы томск

открыть кейсы кс го http://cs-go.ru

Нужен качественный бетон? beton-moscvich.ru быстро, надёжно и по выгодной цене! Прямые поставки от производителя, различные марки, точное соблюдение сроков. Оперативная доставка на стройплощадки, заказ онлайн или по телефону!

2 знака зодиака, от которых практически невозможно что-либо скрыть

https://pin.it/1l95y2WeH

Нужна машина в прокат? аренда авто стамбул без депозита быстро, выгодно и без лишних забот! Машины всех классов, удобные условия аренды, страховка и гибкие тарифы. Забронируйте авто в несколько кликов!

Статьи о ремонте и строительстве https://tvin270584.livejournal.com советы, инструкции и лайфхаки! Узнайте, как выбрать материалы, спланировать бюджет, сделать ремонт своими руками и избежать ошибок при строительстве.

unpacking services toronto movers toronto

Эти четыре знака Зодиака накроет волна счастья уже на этой неделе

https://www.pinterest.com/pin/957366833290452816/

химчистка мебели

химчистка мебели

Перспективы финансов: https://123inv.ru

Успешные кейсы применения финансов: https://triumph-uk.ru

Букет собран с душой, огромное спасибо!

заказать цветы с доставкой в томске

http://alexey-savrasov.ru/records/articles/filmu_o_poiske_sokrovish_besplatno.html смотреть фильмы и сериалы онлайн бесплатно без регистрации в хорошем качестве

https://myasnayatarelka.ru Мемы про финансы.

Как реализовали финансов в компании: https://krovlyaug.ru

Лучший женский журнал https://modam.com.ua онлайн! Мода, стиль, уход за собой, фитнес, кулинария, саморазвитие и лайфхаки. Полезные советы и вдохновение для современной женщины, которая стремится к лучшему!

Ваш гид по стилю https://magictech.com.ua красоте и жизни! Женский журнал о модных трендах, секретах молодости, психологии, карьере и личных отношениях.

http://devec.ru/Joom/pgs/filmu_144.html фильм триггер смотреть онлайн бесплатно 1 сезон

Bu burcl?r pula daha meyillidir https://www.pinterest.com/pin/957366833290413195

Когда состоится встреча Путина и Трампа? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QaQAFGjNvyM

http://vip-barnaul.ru/includes/pages/onlayn_filmu___komfort_i_dostupnost_v_mire_kinematografa.html тихое место на реке 4 букв

http://vip-barnaul.ru/includes/pages/onlayn_filmu___komfort_i_dostupnost_v_mire_kinematografa.html девушки у него на втором плане 6 букв

Лучший женский онлайн-журнал https://sweetheart.kyiv.ua Всё о моде, красоте, здоровье, отношениях и успехе. Экспертные советы, лайфхаки и мотивация для уверенных в себе женщин.

find more information

hot wallet

Which Zodiac signs should be careful – a dangerous period begins tomorrow!

https://www.pinterest.com/pin/957366833290379120

Авто портал для всех https://rupsbigbear.com кто любит автомобили! Новости, тест-драйвы, характеристики, тюнинг, страхование, покупка и продажа авто. Следите за последними тенденциями и выбирайте лучшее для себя!

Автомобильный сайт https://newsgood.com.ua для водителей и автолюбителей! Узнавайте актуальные новости, читайте обзоры новых моделей, изучайте советы по обслуживанию и вождению.

Выявлен фрукт, который является природным эликсиром молодости https://www.pinterest.com/pin/957366833290370789

Сайт для женщин https://womanexpert.kyiv.ua которые хотят быть успешными и счастливыми! Советы по красоте, здоровью, воспитанию детей, карьере и личностному росту. Актуальные тренды, лайфхаки и вдохновение для современных женщин!

Портал для женщин https://woman365.kyiv.ua которые ценят красоту и уверенность! Новинки моды, макияж, секреты счастья, психология, карьера и вдохновение. Узнавайте полезные советы и воплощайте мечты в реальность!

Женский онлайн-журнал https://krasotka.kyiv.ua мода, красота, здоровье, семья и карьера. Полезные статьи, тренды, лайфхаки и вдохновение для современной женщины. Читайте, развивайтесь и наслаждайтесь жизнью!

available movers toronto movers toronto

Современный женский сайт https://dama.kyiv.ua красота, стиль, здоровье, семья и карьера. Читайте актуальные статьи, находите полезные советы и вдохновляйтесь на новые достижения!

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

Детский портал о здоровье https://run.org.ua полезная информация для заботливых родителей! Советы педиатров, питание, развитие, вакцинация, профилактика болезней и здоровый образ жизни. Всё, что нужно знать о здоровье вашего ребенка!

Современный женский портал https://womanlife.kyiv.ua мода, стиль, красота, здоровье, отношения и карьера. Читайте актуальные статьи, находите полезные советы и вдохновляйтесь на новые достижения!

Выбор недвижимости в Киеве https://odinden.com.ua на что обратить внимание? Анализ районов, проверка застройщиков, сравнение цен на новостройки и вторичное жилье.

Лучший женский портал https://rosetti.com.ua Стиль, красота, здоровье, семья, карьера и саморазвитие. Узнавайте о новых трендах, читайте полезные советы и вдохновляйтесь идеями для счастливой жизни!

Temukan keindahan dan keunikan batu hijau yang menjadi pilihan utama dalam koleksi batu alam berkualitas tinggi di situs kami

Все автомобильные новости https://nmiu.org.ua в одном месте! Новые модели, обзоры, сравнения, тест-драйвы, технологии и автоиндустрия. Следите за тенденциями и оставайтесь в курсе событий автопрома!

Новости шоу-бизнеса https://mediateam.com.ua мода, красота и афиша – всё в одном месте! Узнавайте о главных событиях, свежих трендах и топовых мероприятиях. Будьте в курсе всего, что происходит в мире стиля и развлечений!

Выбираем недвижимость в Киеве https://automat.kiev.ua как оценить район, новостройки и вторичный рынок? Анализ цен, проверка застройщика, юридическая безопасность сделки. Полезные советы для покупки квартиры без ошибок и переплат!

Follow UFC fights with https://t.me/s/ufc_ar full tournament schedule, fight results, fighter ratings and analytics. Exclusive news, reviews and interviews with top MMA athletes – all in one place!

https://school33-perm.ru/media/pgs/?hitu_amediateki.html поль мориа крестный отец скачать

Dapatkan pengalaman berkendara terbaik dengan berbagai pilihan mobil mewah di Indonesia di Koko Autos

https://yarkompany.ru/language/pages/?volshebnue_skazki___okna_v_mir_chudes.html посмотреть хорошее кино онлайн бесплатно в хорошем качестве

Untuk mengetahui lebih lanjut tentang harga jam tangan Rolex terbaru, kunjungi situs kami yang memberikan informasi terlengkap tentang koleksi jam tangan mewah ini

https://abis-prof.ru/image/pgs/index.php?filmu_onlayn_besplatno_v_horoshem_kachestve.html великая леди фантастики 6 букв

Good day! I could have sworn I’ve visited this site before but

after browsing through some of the posts I realized it’s new to me.

Anyways, I’m definitely pleased I found it and I’ll

be bookmarking it and checking back regularly!

Займ онлайн официальный сайт микрозаймов

Займ срочно на карту без отказа и проверок микрозайм онлайн на карту без проверок

Купить права Москва

стоимость проката авто аренда авто в симферополь без водителя недорого

case battle

This was such an engaging read! The way you explain everything in a clear, step-by-step manner makes it easy to absorb. I appreciate the actionable advice you provided, and the inviting tone made it all the more enjoyable. Excited to see what you write about next!

oknews360.com

Купить водительские права официально

https://www.llanelliherald.com/

http://olondon.ru/include/pgs/?serialu_pro_sverhsposobnosti__mir_udivitelnuh_vozmozghnostey.html х ф движение вверх смотреть онлайн бесплатно в хорошем качестве

Купить права

http://olondon.ru/include/pgs/?serialu_pro_sverhsposobnosti__mir_udivitelnuh_vozmozghnostey.html смотреть сериал пес 1 сезон бесплатно

Great web site you’ve got here.. It’s hard to find high-quality writing like yours nowadays. I really appreciate people like you! Take care!!

verything is very open with a clear clarification of the issues. It was truly informative. Your website is very helpful. Thank you for sharing.

jaycitynews.com

Инвестиции в жильё: с чего начать? Читайте проверенные советы https://crystalit34.ru/

Как выбрать надёжного застройщика? Полезные рекомендации — https://bti-nsk.ru/

Новостройки или вторичка? Полезные рекомендации — https://an-rusdom.ru/

Хотите сдать квартиру в аренду? Полезные статьи и советы — https://xn--j1aihe7cc.com/

Инвестиции в жильё: с чего начать? Узнайте подробности https://xn—-7sbhyegsibavlngp.xn--p1ai/

Хотите сдать квартиру в аренду? Полезные статьи и советы — https://xn—–7kcoqeea0aaiqm4apq0s.xn--p1ai/

Хотите разбираться в рынке недвижимости? Читайте проверенные советы https://xn—–7kchcrgop2a1bbbeqft7m5b.xn--p1ai/

Инвестиции в жильё: с чего начать? Полезные рекомендации — https://xn—-8sbqbliyb2m.xn--p1ai/

Хотите сдать квартиру в аренду? Полезные статьи и советы — https://xn——6cdbaabncc2b3blicg2a2b7axf0dzfui.xn--p1ai/

Новостройки или вторичка? Узнайте подробности https://xn--90aimcoinaikf.xn--p1ai/

I absolutely loved reading this! It was insightful, inspiring, and incredibly well-written. Your ability to break down complex topics in a way that’s engaging and accessible is truly commendable. The real-life examples and actionable tips made the content even more valuable. It’s rare to find writing that both educates and motivates readers to take action. I’m looking forward to reading more—keep up the amazing work!

Покупка квартиры без рисков? Узнайте подробности https://xn—-7sbccdscdoffrg1cybj3z.xn--p1ai/

Driving school in UK – Watford – IQ Driving School

https://www.iqdrivingschool.co.uk/

Watford driving lessons – IQ Driving School

https://www.iqdrivingschool.co.uk/packages

https://www.google.com/maps/place//data=!4m3!3m2!1s0x48766b58ac4f11e5:0x44c76a11738ab50b!12e1?source=g.page.m.kd._&laa=lu-desktop-review-solicitation

Купите теплицу https://tepl1.ru с доставкой по выгодной цене! Широкий выбор моделей: поликарбонатные, стеклянные, пленочные. Быстрая доставка, прочные конструкции, удобный монтаж. Идеально для дачи, сада и фермерства. Заказывайте качественные теплицы с доставкой прямо сейчас!

Your comment is a wonderful example of thoughtful feedback. Thank you!jili game

https://logospress.ru/content/pgs/?filmu_slesheru__istoriya__osobennosti_i_vliyanie_na_kulturu.html на каком сайте смотреть фильмы бесплатно в хорошем качестве можно и без регистрации

Dobrodosli v hotel v Kolasin! Uzivajte v udobnih sobah, osupljivem razgledu in odlicni storitvi. Pozimi – smucanje, poleti – pohodi v gore in izleti. Prirocna lokacija, restavracija, SPA in prijetno vzdusje. Rezervirajte nepozabne pocitnice!

Najboljse pocitnice hotel Pavlovic Zabljak! Uzivajte v udobju, svezem zraku in osupljivi pokrajini. Gorske poti, smucanje, izleti in prijetno vzdusje. Brezplacen Wi-Fi, zajtrk in parkirisce. Rezervirajte bivanje v osrcju narave!

A remarkable post that stands out in every way! The level of detail and thought put into this is evident, making it both an enriching and enjoyable read. The way information is structured and delivered makes it highly accessible while maintaining depth. Your ability to create such compelling content is truly commendable—keep the excellence going.

I just wanted to take a moment to thank you for such a wonderful post. Your ability to explain complex topics in such a clear and concise way is truly impressive. You’ve managed to make something potentially overwhelming feel both accessible and enjoyable to read. I also appreciate how relatable and down-to-earth your tone is. I’m sure many of your readers, myself included, are grateful for the valuable insights you’ve shared.

This blog post is an excellent example of insightful and impactful writing that not only educates but also inspires readers. From start to finish, the clarity and depth of your arguments shine through, making this a truly enjoyable read. It’s clear that a lot of thought and effort has gone into crafting this piece, and the result is a compelling and engaging exploration of the topic at hand.

криминальная россия крмп samp fix

OpenMP скачать самп 0 3

ипотека и покупка недвижимости https://magnk.ru что нужно знать? Разбираем выбор жилья, условия кредитования, оформление документов и юридические аспекты. Узнайте, как выгодно купить квартиру и избежать ошибок!

The rental price is relatively low considering californiarent24.com the conditions of the particular country and the market situation. The cars are affordable for most tourists.

holidaynewsletters.com

Asking questions are genuinely fastidious

thing if you are not understanding anything totally, however

this post gives nice understanding even.

http://spincasting.ru/core/art/index.php?filmu_pro_biznes__vdohnovenie_i_uroki_dlya_predprinimateley.html смотреть новинки в хорошем качестве бесплатно онлайн

belfastinvest.net

Select the pick-up point for the car, birminghamnews24.com and indicate the drop-off location if you plan to travel around the country.

https://histor-ru.ru/wp-content/pgs/serialu_pro_turmu___zahvatuvaushiy_mir_za_resh_tkoy.html сальваторе адамо падает снег видео

https://www.urank.ru/pgs/dlinnue_serialu___pochemu_mu_ih_tak_lubim_.html смотреть онлайн бесплатно в хорошем качестве волк с уолл стрит

What a fantastic blog! The information is incredibly well-presented, making it enjoyable to read. The depth of research and attention to detail make a huge difference. The way complicated subjects are broken down into easily digestible pieces is commendable. Your passion for sharing knowledge is evident in every post. This blog is a valuable resource for anyone seeking quality information. Keep up the amazing work! I look forward to reading more insightful content in the future. Wishing you continued success and growth. Thanks for sharing such well-crafted and informative posts.

https://www.urank.ru/pgs/dlinnue_serialu___pochemu_mu_ih_tak_lubim_.html свежие фильмы смотреть бесплатно в хорошем качестве

шаффл танец для начинающих https://opendance.ru

Мир компьютерных игр https://lifeforgame.ru/ Мы расскажем о лучших новинках, секретах прохождения, системных требованиях и игровых трендах. Новости, гайды, обзоры и рейтинги – всё, что нужно геймерам.

detroitapartment.net

Such an informative post! I love how you took a complicated topic and made it easy to understand. Your approach is clear and concise, yet thorough, and I can’t wait to dive deeper into the subject. The examples you included were particularly helpful, and I found myself nodding along as I read. I’ll definitely be bookmarking this post for future reference. Thanks for sharing your knowledge in such an accessible way, and I’m looking forward to your next post!

https://astorplace.ru/wp-content/pgs/filmu_onlayn___novuy_uroven_domashnego_kinoteatra.html какие фильмы или мультфильмы можно посмотреть

They can be sown in the autumn arizonawood.net, after harvesting, or in early spring before sowing.

qled телевизор 4k ultra hd samsung https://televizory-qled.ru

обучение стрип пластике студия стрип пластики

https://naturalbeekeeping.ru/wp-content/pgs/filmu_140.html смотреть самые интересные фильмы новинки

Все о недвижимости https://poselok-exclusive.ru покупка, аренда, ипотека. Разбираем рыночные тренды, юридические тонкости, лайфхаки для выгодных сделок. Помогаем выбрать квартиру, рассчитать ипотеку, проверить документы и избежать ошибок при сделках с жильем. Актуальные статьи для покупателей, арендаторов и инвесторов.

Все о недвижимости https://komproekt-spb.ru покупка, аренда, ипотека. Разбираем рыночные тренды, юридические тонкости, лайфхаки для выгодных сделок. Помогаем выбрать квартиру, рассчитать ипотеку, проверить документы и избежать ошибок при сделках с жильем. Актуальные статьи для покупателей, арендаторов и инвесторов.

repairdesign24.com

tokyo365web.com

http://kuzovkirov.ru/wp-content/pgs/romanticheskie_komedii__spisok_luchshih_smeshnuh_filmov_o_lubvi.html кино смотреть онлайн бесплатно в хорошем качестве без рекламы

https://lepidopterolog.ru/media/pgs/kinovselennaya_marvel__istoriya__filmu_i_vliyanie_na_pop_kulturu.html ютуб смотреть фильмы в хорошем качестве бесплатно

https://ecotruck.su/images/pgs/iz_rossii_s_lubovu__kino_90_h.html смотреть новинки бесплатно в хорошем качестве

Дізнавайтеся про останні новини https://ampdrive.info електромобілів, супекарів та актуальні події автомобільного світу в Україні. Ексклюзивні матеріали, фото та аналітика для справжніх автолюбителів на AmpDrive.?

Хотите разбираться в рынке недвижимости? Читайте проверенные советы https://crystalit34.ru/

There is an option for organic invest-company.net soil fertilization by growing plants.

Buckwheat crops are planted on poor construction-rent.com soils to increase the content of phosphorus and potassium.

Инвестиции в жильё: с чего начать? Полезные рекомендации — https://bti-nsk.ru/

Инвестиции в жильё: с чего начать? Полезные рекомендации — https://an-rusdom.ru/

сосет под мефом порно измена

Инвестиции в жильё: с чего начать? Полезные рекомендации — https://anplatinum.ru/

В предверии праздника искал где купить цветы, нашёл этот магазин Доставка цветов в Томске теперь всегда буду заказывать здесь

Как выбрать надёжного застройщика? Читайте проверенные советы https://an-gavan.ru/

Хотите разбираться в рынке недвижимости? Полезные рекомендации — https://amkproekb.ru/

Новостройки или вторичка? Полезные статьи и советы — https://agape-dom.ru/

Такси для бизнеса https://www.province.ru/karera-sovety-spetsialista/rabota-v-yandeks-taksi-sovety.html работа по всей России. Удобные поездки для сотрудников! Оформите корпоративный аккаунт и получите выгодные условия, детальную отчетность и надежный сервис. Быстрое бронирование, прозрачные тарифы, комфортные автомобили – организуйте рабочие поездки легко!

Такси для бизнеса http://www.obzh.ru/mix/korporativnye-puteshestviya-s-yandeks-taksi-novoe-slovo.html работа по всей России. Удобные поездки для сотрудников! Оформите корпоративный аккаунт и получите выгодные условия, детальную отчетность и надежный сервис. Быстрое бронирование, прозрачные тарифы, комфортные автомобили – организуйте рабочие поездки легко!

https://turbocomp.ru/images/pgs/kiberpank__mir_budushego_na_grani_tehnologiy_i_chelovechnosti.html мальтипу собака купить в челябинске

Покупка квартиры без рисков? Узнайте подробности https://acb-house.ru/

Товары для вашего авто https://avtostilshop.ru автоаксессуары, масла, запчасти химия, электроника и многое другое. Быстрая доставка, акции и бонусы для постоянных клиентов. Подбирайте товары по марке авто и будьте уверены в качестве!

Товары для вашего авто avtostilshop.ru автоаксессуары, масла, запчасти химия, электроника и многое другое. Быстрая доставка, акции и бонусы для постоянных клиентов. Подбирайте товары по марке авто и будьте уверены в качестве!

Хотите разбираться в рынке недвижимости? Читайте проверенные советы https://3909102.ru/

365newss.net

купить игровой ноутбук в туле купить игровой ноутбук в москве недорого

https://olimp-yug.ru/media/pgs/smotret_filmu_v_horoshem_kachestve_besplatno_onlayn.html торенты ру бесплатные скачать фильмы

Ваш гид по дизайну https://sales-stroy.ru строительству и ремонту! Советы профессионалов, актуальные тенденции, проверенные технологии и подборки лучших решений для дома. Всё, что нужно для комфортного и стильного пространства, на одном портале!

Ипотека без сложностей https://volexpert.ru Наши риэлторы помогут выбрать идеальную квартиру и оформить ипотеку на лучших условиях. Работаем с топовыми банками, сопровождаем сделку, защищаем ваши интересы. Делаем покупку недвижимости доступной!

В предверии праздника искал где купить цветы, нашёл этот магазин купить цветы томск теперь всегда буду заказывать здесь

гайд игры играть красивые дома в майнкрафте поэтапно

плей прохождение игры крутые дома в майнкрафте схемы

Each model has a comfortable newsprofit.info interior and equipment that allows you to experience the convenience of traveling over various distances.

Надоели одни и те же фильмы? На hdrezka.day тебя ждут сотни кинолент — от угарных комедий до триллеров, от которых немеют ноги! Включайте в 4K, без смс, хоть с утра — очереди завидуют! Бегите на Смотреть шдрездка — этот архив растёт как вселенная Marvel! Команда супер-рады тебе — попробуйте!

Just wish to say your article is as astonishing. The clearness in your post is just spectacular and i can assume you’re an expert

on this subject. Well with your permission let me to grab your

RSS feed to keep updated with forthcoming post. Thanks a million and

please keep up the enjoyable work.

полное прохождение игры как включить счетчик фпс в кс

игра прохождение заданий киберпанк 2077 сюжет игры

Your point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you. https://accounts.binance.com/hu/register?ref=FIHEGIZ8

?? Кино-вечеринка без правил! Приглашаем на kinogo.uk — тут всё можно: Смотреть фильмы в HD; Рвать шаблоны от эксклюзивов;

Sa amin, mas malaking premyo, mas malaking saya!!!…War Of Dragons

ссылка на сайт кракен kraken.cc

купить тюльпаны цветы с доставкой спб

купить цветок продажа цветов

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me? https://www.binance.info/en-IN/register?ref=UM6SMJM3

Последние IT-новости https://notid.ru быстро и понятно! Рассказываем о цифровых трендах, инновациях, стартапах и гаджетах. Только проверенная информация, актуальные события и мнения экспертов. Оставайтесь в центре IT-мира вместе с нами!

Последние IT-новости https://notid.ru быстро и понятно! Рассказываем о цифровых трендах, инновациях, стартапах и гаджетах. Только проверенная информация, актуальные события и мнения экспертов. Оставайтесь в центре IT-мира вместе с нами!

взять микрозаем онлайн сайт займ

займ кредит деньги займ онлайн

Страхование по лучшей цене https://осагополис.рф Сравните предложения страховых компаний и выберите полис с выгодными условиями. Удобный сервис поможет найти оптимальный вариант автострахования, ОСАГО, КАСКО, туристических и медицинских страховок.

ссылка на кракен в браузере kra31.cc

кракен магазин зеркало кракен маркетплейс вход

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks! https://accounts.binance.com/uk-UA/register-person?ref=W0BCQMF1

кракен маркетплейс ссылка на сайт кракен сайт вход

https://компаниярегионстрой.рф

кракен зеркало 2025 Кракен как зайти

Spolehlive stehovani Stehovani bytu rychle

macbook air 13 m2 8gb macbook air 13 m2 512gb

ноутбук apple macbook air 13 m2 8 https://macbook-air-m2.ru

Грузчики в Праге Перевозка мебели надежная помощь при переездах и погрузке. Аккуратная работа, доступные цены, оперативное выполнение заказов. Обращайтесь за профессиональными услугами!

Levny odvoz nabytku Stehovani bytu rychle

https://жк-ярд.рф

https://guldog.ru

Профессиональный выгул собак https://guldog.ru забота, активность и безопасность для вашего питомца! Наши догситтеры позаботятся о комфортной прогулке, играх и движении. Индивидуальный подход, удобное время и фотоотчеты.

снять яхту яхта в дубае

аренда катера с каютой arenda-yaht-spb.ru

аренда яхты в дубае аренда яхты

снять катер на день рождения аренда яхты в питере

https://active-clean.ru/

macbook pro 14 16 гб macbook pro 16 core

macbook air 2023 256 apple macbook air 15.3 2023

macbook pro 14 16 1tb macbook pro 16 m4 max

macbook air 2023 256 apple macbook air 15.3 2023