Mary Bartlett came to Dartington in 1963 as a horticultural student. After her training she became responsible for the glasshouses, nursery and walled garden.

Mary Bartlett came to Dartington in 1963 as a horticultural student. After her training she became responsible for the glasshouses, nursery and walled garden.

She is the author of several books, including the monograph Gentians, and Inky Rags, a review of which can be found on the Dartington website. She is now the tutor for bookbinding in the Craft Education department. More blogs from Mary

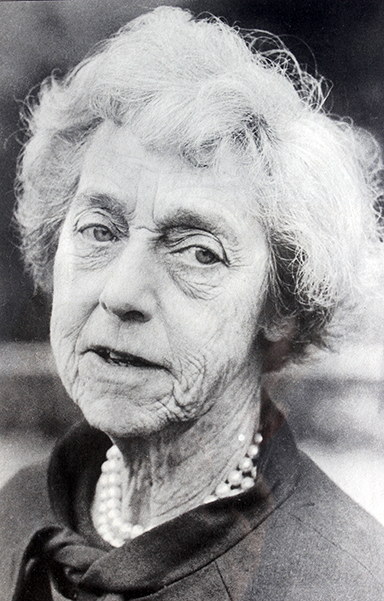

Every evening when I turn the key in my workshop door, I say goodnight to the photograph of Dorothy Elmhirst that hangs on the wall beside it.

Tonight, when I got back home, I noticed the bird feeder was empty, and I was collecting a refill when I felt the brush of a bird wing against my cheek. The sparrow hawk couldn’t have seen me behind the shed corner, and so it misjudged its evening surprise attack. Or maybe not!

I felt fortunate to have had such a close primal encounter. Like the photograph by the door, it reminded me to try to ‘keep it real’.

Mention Dorothy Elmhirst’s name at Dartington and the routine response is to smile about her fabulous wealth and her delight in spending it well. If only it wasn’t all gone! And so we miss the point.

A century on from the start of the First World War, when there’s a passing interest in re-assessing reasons and motives, suppose we consider the real reasons for Dartington – lest we forget.

“(Dorothy)had an inheritance but worried about how had he made it, and how she was to spend it.”

Dorothy’s mother died when she was six. Her father re-married, only to lose his second wife in a riding accident when Dorothy was 18. When he became ill and subsequently died, Dorothy was with him.

It left her an orphan in 1904. She had an inheritance but worried about how had he made it, and how she was to spend it.

In 1918, while he was on the margins of the League of Nations peace conference that was supposed to put an end to war, her first husband, Willard, died in the influenza epidemic.

She was to have gone to meet him in Paris within two weeks. It left her with three young children. When Leonard Elmhirst found her in 1920, he was suffering too. He had lost two brothers in the fighting – and down with them went his religion.

This was the sorrowful legacy Dartington’s utopianism was built upon, and it helps to explain how one of the Elmhirsts’ most successful entrepreneurial adventures came about…

“Leonard walked around the grounds, alone for two hours in the midwinter dark…

One Sunday midnight in 1928 the publisher Harold Monro, champion of the war poets, telephoned his friend, the theatre producer Maurice Browne, and told him about a wonderful play he has just seen in preview – which he must, please rescue from obscurity.

He persuaded Browne to read the script. It’s called Journey’s End, and it’s a bleak, unvarnished account of life and death in a front-line dugout. Browne got the train to Dartington and read the play to the Elmhirsts.

Afterwards Leonard walked around the grounds, alone for two hours in the midwinter dark…

Within a year, and now with the Elmhirsts’ crucial backing, Journey’s End had been performed by 76 companies in 25 languages. Its West End run of 593 performances was the longest ever at that time.

Dartington acquired two Shaftesbury Avenue theatres with the proceeds. And although the writer, R.C. Sherriff, protests he was writing about ordinary heroism rather than pacifist propaganda, improving hindsight turns Journey’s End into a key political text. “It hits the hardest blow in its swollen stomach that war has yet had” the novelist Hugh Walpole observed.

Browne himself said of the Elmhirsts: “There was no trace of swank about either of them”.

Maurice Browne is buried in the Dartington village churchyard not far from my husband Bram. I cut the grass there sometimes and when I walk back through the gardens, I thank Dorothy for her kindness and compassion. It has shaped my life here.

If you would like to hear how the Elmhirsts sounded in real life, our History & Archives page contains recordings of both Leonard and Dorothy speaking at Foundation Day in 1967.

Mary comments: “I can still see her giving that talk in the great hall.”