Mary Bartlett came to Dartington in 1963 as a horticultural student. After her training she became responsible for the glasshouses, nursery and walled garden.

Mary Bartlett came to Dartington in 1963 as a horticultural student. After her training she became responsible for the glasshouses, nursery and walled garden.

She is the author of several books, including the monograph Gentians, and Inky Rags, a review of which can be found on the Dartington website. She is now the tutor for bookbinding in the Craft Education department. More blogs from Mary

One of my favourite rhododendrons, the dizzyingly fragrant Lady Alice Fitzwilliam, is in flower outside my living room window, reminding me that in the Dartington Hall Gardens early May is the perfect time.

Dorothy Elmhirst thought so. “This is the peak of the year”, she wrote in her notebooks in May 1954, “the ecstatic month when each day brings a deeper realization of beauty”.

And again in 1962: “I think this is the most utterly moving and beautiful moment I have ever known here”.

The rhododendron Lady Alice Fitzwilliam was one of Dorothy’s favourites, too. It is a hybrid with a faultless pedigree – created at the Fitzwilliam family mansion, Wentworth Castle, from a variety of the Edgeworthia species.

It was discovered in the Sikkim Himalayas in 1849 by Joseph Hooker and named after another great adventurer-botanist of the period, the Indian Civil Servant Michael Pakenham Edgeworth. Edgeworth, half sister of the novelist Maria, endeared himself to me no end by writing and illustrating an extraordinary monograph on pollen.

So the bubbling pink-white blossom of Lady Alice Fitzwilliam reminds me of the link between the English garden and English colonial power (and that exotic plant collections were a demonstration of imperial virtue that alas all too often disguised imperial cruelty).

More vividly than today’s visitors are likely to know, the survival here of the Fitzwilliam rhododendron also remembers the closeness there once was between Dartington and the great experimental botanical gardens at Cambridge and Kew.

In the years between the wars, the Dartington Estate might have become a rival to Kew – not only because it maintained a marvellous garden oasis at the geographical heart of the social experiment, but also because it was putting botanical horticulture and its connections with science, food production, medicine and entrepreneurship at the centre of the commercial and educational development plan.

The one chosen to develop the Estate on such ambitious lines was Stewart Lynch, today a rather neglected figure, overshadowed by the bigger names in Dartington garden design like Percy Cane and the classy American import Beatrix Farrand.

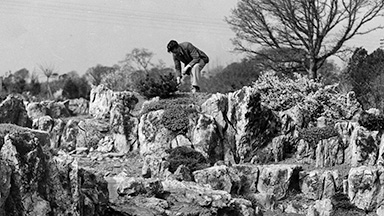

Yet most of the familiar features of today’s gardens – the sunny border, the heather steps, the modern tiltyard – were established during Stewart Lynch’s tenure.

Much more widely across the Estate landscape, he also supervised the development and extension glasshouses, nurseries, and landscaping and garden furniture businesses.

Recommended to the Elmhirsts by the then Director at Kew, Lynch had just the right skill-set to realise his and Leonard’s hopes of marrying business with scientific and educational experiment.

He was the son and grandson of Kew gardeners. His father, Richard Irwin Lynch, was furthermore a significant figure among British botanical horticulturalists.

He was foreman of the Kew tropical house and ran a propagation unit that helped to extend the colonial rubber trade. When he moved from Kew to Cambridge it was on the recommendation of Joseph Hooker himself.

Lynch junior started his own career at Cambridge but went to Europe in the early years of the 20th century to be groomed for a job as utopian as the one the Elmhirsts entrusted to him in 1928.

By then he had trained in Paris with the landscape architect, Rene Andre, whose family business influenced the spread of city parks right across Europe as far as Vilnius.

He learned plantsmanship with the clematis specialist Francisque Morel, and he was a student gardener on Alice de Rothschild’s estate at Grasse, Cannes, a famous hangout of the rich and royal.

At the height of Stewart Lynch’s influence at Dartington, there were nurseries at Huxhams Cross (14 acres), Symmonds Tree (3 acres), Lane End (5 acres), and Bovey Tracey (3 acres).

There were wonderful greenhouses on every site, many of them built by Woods of Taplow. Some of them were still standing when I joined the Gardens department as a trainee in 1963.

Lynch’s team built gardens at the Chelsea Flower Show, winning gold medals in three successive years, and for Dartington’s showing there in 1935 he saw to press an extravagant, comprehensive Dartington Gardens Catalogue.

Copies are still sought after by garden historians everywhere and are the remaining tangible evidence of the scale and ambition of the nursery enterprise. A few of the old illustration blocks survive, too; I know – I rescued them!

What went wrong? So far west of Metroland, the 1930s weren’t a great time for garden making; the Dartington businesses lost money. Then came the war and emergency legislation that turned nurseries into market gardens.

Trust historian Victor Bonham Carter records: “The reserve of ornamental trees, shrubs and plants at Symmonds Tree was scrapped… It was a tragic decision…under pressure from the War Agricultural Executive Committee, which was known to be hostile to Dartington. But this does not excuse an act of folly.”

Lynch became ill with rheumatoid arthritis in 1942 and retired in 1943. I have asked around if anyone remembers him.

The same anecdote has come back from three sources. As an elderly man, he could sometimes be seen sitting in the courtyard enjoying the sun. A penny for his thoughts!

If this blog interested you, you may wish to read Reginald Snell’s book From the Bare Stem: Making Dorothy Elmhirst’s Garden at Dartington Hall (published by Devon Books in association with Dartington Press, available from Dartington Visitor Centre).

So pleased to find your blog. I have just been lucky enough to find one of the catalogues at a car boot sale. I am no gardener but I was attracted by the wood engravings inside, as I collect prints and the blocks (very envious of yours if you have the originals)

Do you know who engraved them. Some have a monogram of Dilly or similar whilst the rest are unmarked.

I would love to know so that I can go hunting for some more.

The exhibition stand photo is wonderful, wish I had been there.

Dear Liz,

thank you for your interest.

I am just sorry I never knew Lynch.

I have tried to find who illustrated the blocks but with no luck. The ones I have are metal blocks so they may have been reproduced from the original art work as for the number of printed ones produced commercially my guess only metal ones would stand the wear and tear on the image.

At some point I hope to go up to our archive in the record office and have another search in the old boxes.

In the coming year hope to work on a book using the blocks and quotes from an American plant breeder called Luther Burbank who before WWII had his named varieties growing in our walled garden.

Anything you find I would be grateful to know.

All best wishes,

Mary Bartlett

Good morning Mary,

You do not know me but I was also a trainee gardener at Dartington but before your time.

Four of us who trained there are still in contact with one another and have had successful careers in horticulture, much of this success can be attributed to Dartington and John Johnson the head gardener who inspired us.

One story that happened when we were there was as follows.

The garden drive which has low walls was being repaired by an estate stone mason, Leonard Elmhurst noticed the mason appeared to have trouble with his work, LE asked what the problem was and was told it was a back problem, he (LE) left and came back a little later with a low stool and told the mason to sit on it whilst he worked. I have always remembered this as it demonstrates a caring person who felt for others including those who laboured at Darlington.

Clive

Dear Clive,

When I first came, I lived with Mr and Mrs Johnson in Gardens Cottage until his sudden death. Mrs Johnson came to stay many times after she had moved to Glasgow where Gordon was at the Botanic Garden I think. I would agree he was an amazing person and was very kind to me. I am interested in the period before he came prior to WWW2 and the major works and planting during that time. Recently I re-read Wilson’s Aristocrats of the Garden published before the war and still on the shelf in the morning room as Dorothy had left it. Looking at the plants mentioned I think it must have been an influence coming from the Arnold Arboretum. Many of her books do have annotations including Will Arnold Fosters book Trees and Shrubs for Milder Counties.

I would always be pleased to have more information /photos of planting/stories like the one you sent.

You may have been here with my brother in law John Bartlett who has spent his time in horticulture in the US.

You may also know my monograph on Gentians published by Blandford. I have written many other small booklets on various things since.

Thank you for making contact.

Mary