Mary Bartlett came to Dartington in 1963 as a horticultural student. After her training she became responsible for the glasshouses, nursery and walled garden.

She is the author of several books, including the monograph Gentians, and Inky Rags, a review of which can be read here. She is now the tutor for bookbinding in the Crafted @ Dartington department. More blogs from Mary

Extinction is usually referenced by looking at the geological record.

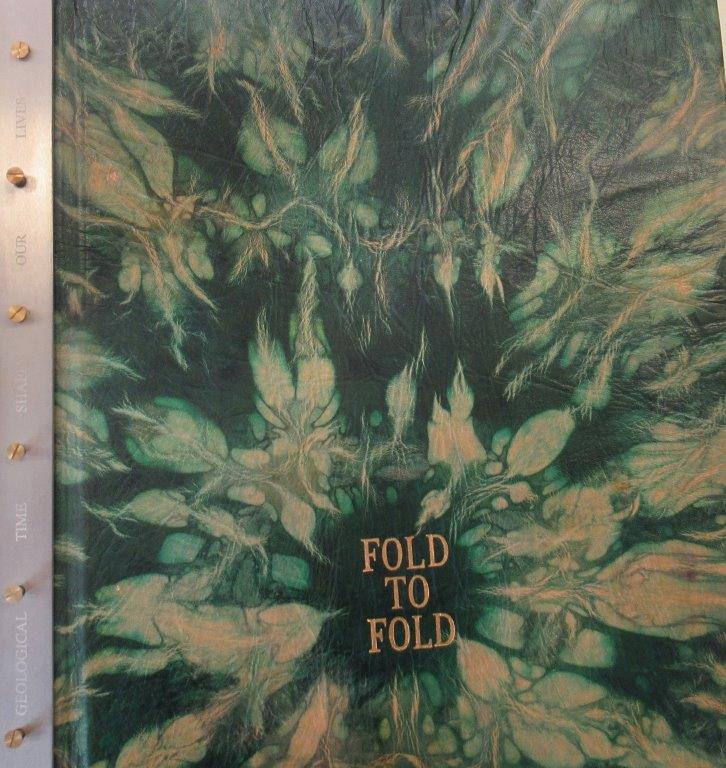

In 2012 I made the binding for a book called Fold to Fold. The leather was batik dyed; the metal bars holding the structure together were engraved on stainless steel. I chose the title to indicate the influence of the folding of strata in rocks, and I used examples from a collection of rare papers to echo the pattern and colour in nature and to celebrate and preserve the skill of marbled paper making.

Tanya Schmoller selecting papers for the collection at Manchester Metropolitan university

Fold to Fold book cover

Fold to Fold video recording

I also wanted to illustrate the complexity – but insignificance – of what we humans will leave in the sedimentary layer. The last page of the book was all about plastic pollution – but by now I ought to be adding a whole new section about the detritus of the coronavirus pandemic – those millions of face-masks and disinfectant bottles, not to mention the still-to-be-discovered effects of hand sanitizer goo and soap wash on our watercourses. The human toll of Covid 19 is being painstakingly recorded; the environmental cost of saving the skins of the rest of us is still to be measured.

This year the bookbinding department notches up its 85th year. Under any other circumstances than these, I would have arranged a small exhibition. We just about managed to run classes for six weeks in the autumn. During that time, I designed a document folder – in case the worst happened – so that my relations could find my will and the other papers they would need to be able to tidy away my leftovers. My class members stoically followed suit, using a glorious variety of colours and decorative papers.

Dartington Hall was built in the late 1300’s by John Holland, half-brother to Richard II. In this time it is worth taking time to pause and read the speech Shakespeare wrote. ‘No matter where. Of comfort no man speak: Let’s talk of graves, of worms and epitaphs:……….Let’s choose executors and talk of wills:’ Richard II, act 3, scene 2.

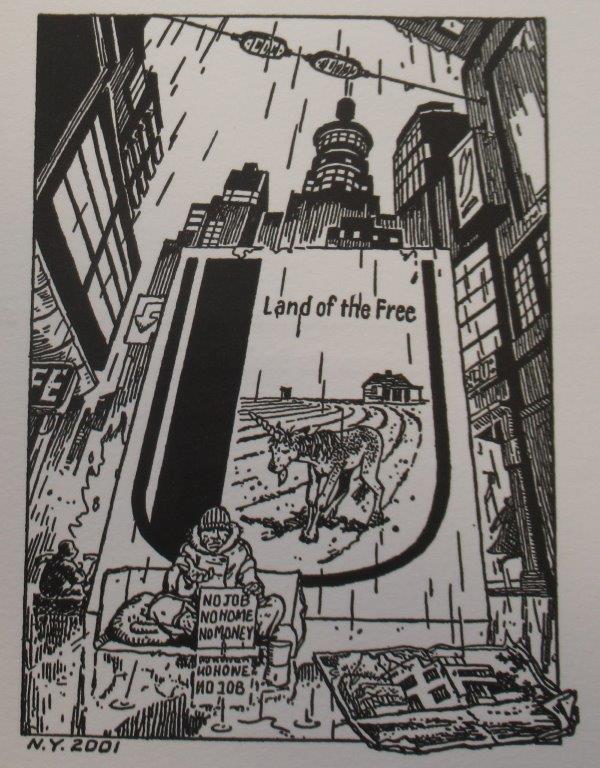

My good friend Paul Johnson, a well-known international book artist, made me a beautiful popup book of the unicorn. (Picture) It would be impossible to commission such an item. In 2019, at the Society of Bookbinders Conference in Bath, I lent him a minute sum of money. This wonderful book was my recompense.

In 1938 the artist Eric Ravilious was asked to illustrate a book called High Street, a wonderful portrait of shops and trades The foreword is worth reading as an observation on the style, pace and richness of town life just before the Second World War. Ravilious was friends with many of the artists and makers of the period. Some of the items Dorothy Elmhirst purchased from him and his circle during Dartington’s own pre-War heyday still survive in the Trust collection.

There’s a reference to Dorothy’s patronage in Ravilious and Co by Andy Friend, published in 2017. She bought two paintings and commissioned papered wardrobes by Tirzah Garwood, Ravilious’s wife. They might have been for her apartment in London.

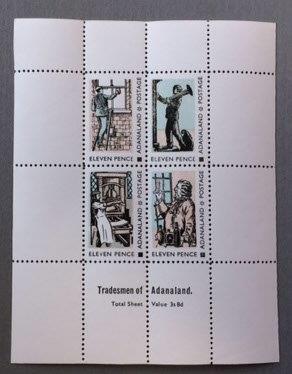

During these past months, high streets everywhere have become places to wander in solitude. Many shops will not survive. Tradesmen – elusive in the best of times – have vanished.

Paul Johnson’s pop up unicorn book

Stamps depicting tradesmen, by Alan Brignull

Eric and Tirzah Ravilious’s son, the photographer James Ravilious, had a long, fruitful relationship with The Dartington Hall Trust. The Trust Archive records how ‘The Beaford Centre, opened in 1966, was initiated by Dartington to serve rural community life through cultural involvement, and public performance’. The Centre remained a Trust department until 1989 when it was endowed as part of a new charitable company, The North Devon Foundation. In 1972, when he was director of the Centre, the late John Lane (who became a Dartington Hall Trust chairman), appointed James Ravilious as Beaford’s resident documentarist. James went on to make an extraordinarily poignant photographic record of a disappearing seam of rural life. A comprehensive account can be found in the book James Ravilious, A Life by his wife, Robin.

Photography played a significant role in another deep crisis, The Great Depression, caused by the fall of Wall Street in 1929. Under President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who came to power in 1933, many rescue initiatives were set up, including, in 1937, The Farm Security Administration. The project established the reputation of a group of great American documentarists and especially that of Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange who photographed the poverty and devastation of the dust bowls on the American Plains caused by the reckless removal of the deep-rooted grasses.

A report in the 1970s warned that nothing had been learned, and another in Science magazine just last month by Roland Pease included photographs of the return of the dust.

Roosevelt also had an interest in forestry, and another of his initiatives, the Civilian Conservation Corps 1933-1942, was responsible for planting millions of trees to try to combat the devastation caused by soil depletion.

Alas, it’s the same story: we haven’t learned; we continue to cut down ancient forests worldwide, to destroy the archive of life and to create dust bowls of industrialisation.

The Whitneys, Roosevelts and Straights were part of the same aristocratic circle in the early 1900s and at the time of Dorothy’s first marriage to Willard Straight. Especially during the 1930s, the Elmhirsts and the Roosevelts were friends and mutual confidants.

Agriculture and forestry in the 1930’s were key aspects of the original Dartington experiment, and forestry, especially in the hands of Leonard Elmhirst’s ‘main man’ Wilfred Hiley, appointed the early 1930s. In his book Woodland Management, 1954, he wrote, ‘It is the duty of each woodland manager to leave his forests in a more ideal condition than he found them’. With hindsight, his strategic investment in the coniferisation of the Dartington woodlands may look reprehensible – but you have to admire the lockdown principle. Primum non nocere At least, do no harm!

The driving force behind conifers was the wartime need for pit props for the Welsh mines. The first-hand account of the woodland can be found in Alice Oswald’s poem Tree Ghosts based on the recollections of Clifford Harris who worked in them all his life. Leonard Elmhirst’s photographic collection is stored in the Dartington Hall Trust archive (see previous article on grey squirrels).

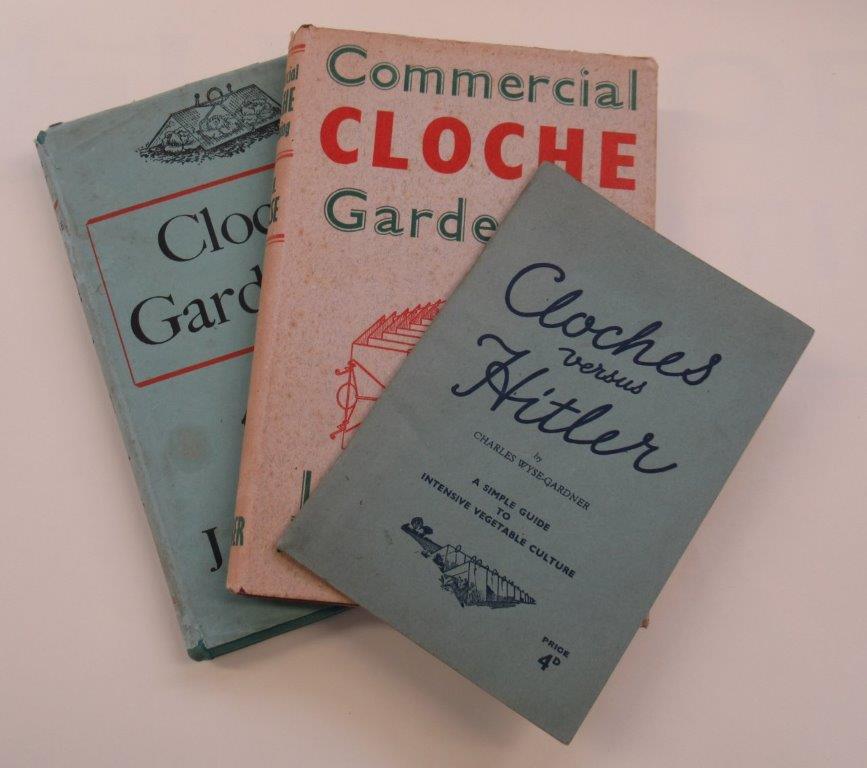

Meanwhile, my open pollinated broad beans, planted according to the moon calendar, have germinated well and I look forward to putting them out under my beloved Chase Cloches, designed back in 1912 by the engineer, Major L. H. Chase. Chase was the inventor also of the wartime slogan ‘Dig for Victory!’ and his glass cloches were the mainstay of commercial horticultural production – before the introduction of plastic.

Pamphlets promoting Chase’s Cloches

Footnote: The government has announced a new plan post Brexit. Environment Land Management.

With thanks to Kevin Mount for editing and Bill Simpson for the photography.

Hеy! Wouⅼd you mind if I ѕhare your blog with my twitter group?

There’s a ⅼot of people that I think would really enjoy yⲟur content.

Please let me know. Thank you

Thank you for your enquiry.

Just ask the Dartington Hall Trust for permission.

Good wishes,

Mary