After our Broadlears adventure in silvoarable – and the general take off of agroforestry across the estate – the one area we’ve wanted to focus on next is silvopasture. This is planting trees in with animals, and often for animals.

Silvopasture delivers all the standard benefits of more trees in the landscape – managing water, improving soil and providing biodiversity habitat – but silvopasture systems also deliver direct benefits to the farm animals themselves. Shade and shelter can improve animal health and welfare, increasing live weight gain, reducing mortality in young stock etc. Where trees are planted as a forage crop they can provide minerals and nutrients otherwise unavailable, and enable livestock to self-medicate through appropriate browsing.

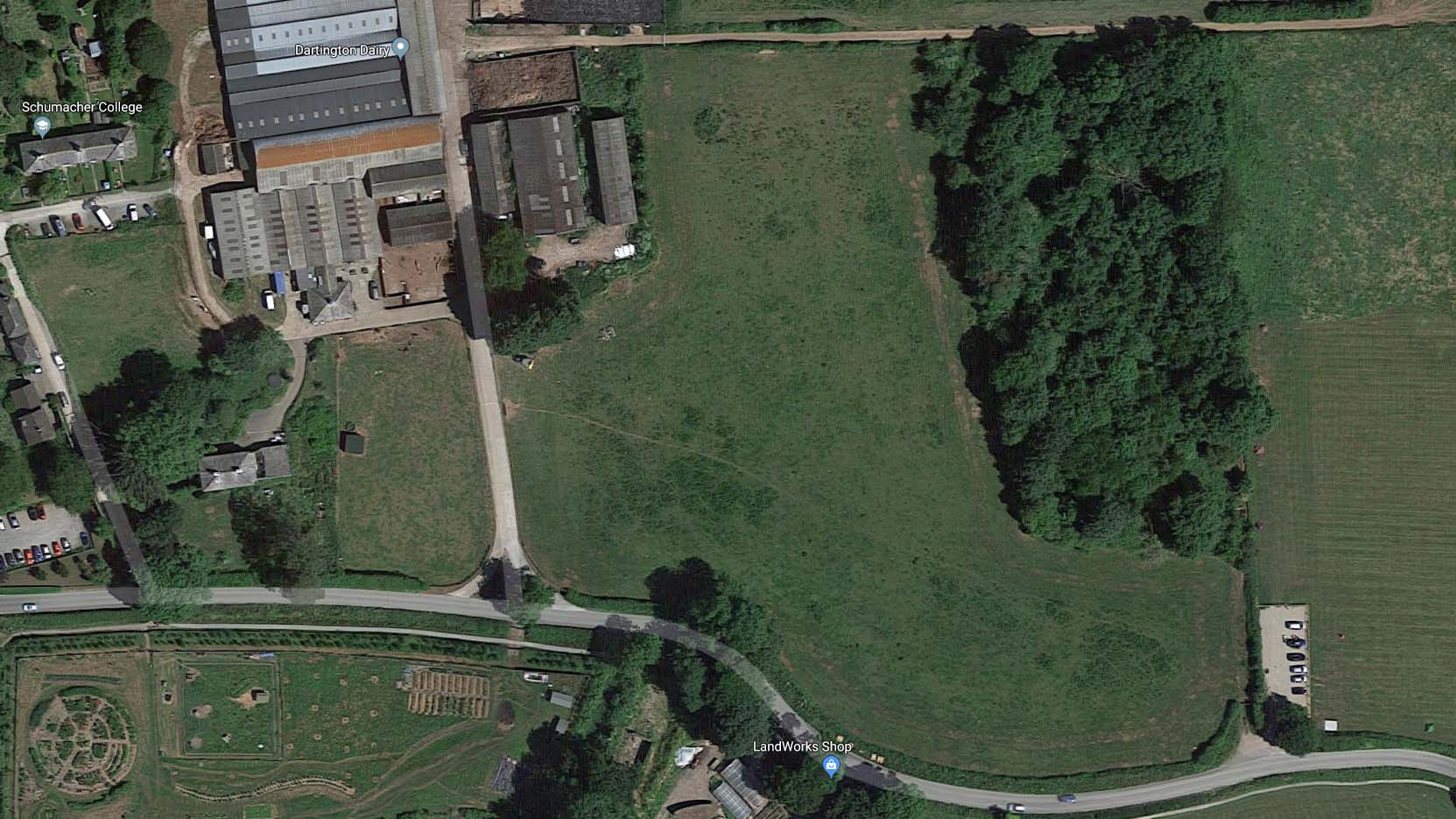

Above: Aerial view of Plum Plot, the site of Dartington’s experiments into silvopasture. Old Parsonage Farm can be seen in the top left corner. Image: Google Maps.

Silvopasture, we felt, would be particularly good for the Dartington Dairy goat herd who generally prefer rougher forage to grass, and have occasionally suffered from worms – something a tree with anthelmintic properties could help.

So…we actually set about trying to cook up a plan for introducing silvopasture quite soon after we finished Broadlears. It’s just that as per last time it took a little while to develop a design and select species and, on this occasion, part of the delay was also me.

Whilst the majority of trees in Broadlears are doing well, the Sichuan peppers I selected have not. As trees are not my specialism to start off, despite progressing the concept of this field I’ve been a bit loathe to plant it for fear of failure. However, at the ever inspirational Oxford Real Farming Conference, any number of speakers declared that if you don’t fail regularly you’re not trying hard enough, so I figured we should once again just crack on, see how it goes and even if it doesn’t always go well at least we’ll again be able to share our learning for the benefit of others.

I’ve also got back into the habitat of insanely long blogs…so dive in and out as suits you.

Harriet Bell (previously food & farming manager at Dartington Hall)

Picking the location

A milking dairy herd is only moved short distances from the main farm, in order to be able to make it to and from the parlour with regularity and without undue stress. This already limits our field options if we’re planting trees as a forage crop for the regular milkers – and we might want to consider letting them browse directly from the trees in future.

A lot of farms have fields where they can put animals to be monitored (because they’re calving, unwell, etc). At Old Parsonage Farm this is Plum Plot. It therefore seemed logical to start here. The increased shade and shelter, plus extra nutritional grazing could have, potentially, the most beneficial impact.

Plum Plot is also positioned at the entrance to the farm and the estate so it’s an accessible location to use as an agroforestry demonstration site.

Lastly, there is a campsite in the adjacent field – so a bit of additional planting gives both the farm and campers some extra privacy.

Picking the crop

As interest in agroforestry increases, there are more and more very helpful resources out there. Some of our top research sources for this project were:

- AGFORWARD

- The Woodland Trust

- The Organic Research Centre

- The Farm Woodland Forum

- The Oxford Real Farming Conference live event and archives

- Our team on the ground here, including Schumacher College, Timber Strategies and Sawmills Devon

- Site visits to places like The Allerton Project

- Chatting to people, lots, in real life and online

- The online fodder tree database for Europe

As with our last agroforestry endeavour, it was easy to feel overwhelmed by the multiplicity of options presented. As this is an initial silvopasture project on a relatively small area of the farm, we thought we’d go for a high level of diversity in the trees and use it as an opportunity to observe how both goats and cows interact with different options. This could then inform more intensive plantings of specific tree types in future.

Going for diversity also helps increase the resilience of the planting in the face of pests, disease and climate change – the hope is something is always likely to survive whatever challenges the trees may face! To that end we’ve also included some non-natives, which may be more resilient in the face of the temperatures and droughts, which are likely to increase in an era of climate change.

Lastly, a diversity of trees fits with the idea of this planting being a nutritional ‘salad bar’ of browsing options – enabling livestock to pick the tree which contains something they particularly need.

Having read, listened and asked a lot of questions about which trees to plant, the eventual plan was to have 24 trees – 12 of which would be standing trees to be potentially pollarded as forage. We decided to opt, in the end, for: Common alder, Italian alder, Small leaved lime, Wych elm, Hornbeam, Sycamore, Sweet chestnut, Beech, Black locust, Aspen, White mulberry and Red mulberry.

The plan is to intersperse these with 12 different varieties of basketry willow which can be coppiced low and sourced on the estate.

Deciding on the layout

As far as I can figure out (illuminate me if I’ve missed something) there are roughly four options for infield tree planting:

- Natural regeneration or planting to mimic natural regen through random positioning. Great for some areas, filling in odd-shaped field corners for example, but problematic if you are ever likely to want to plough, reseed, roll the ground and generally carry out conventional farm practices. In terms of costs, fencing out a corner in order to enable trees to establish can be done relatively easily.

- Planting individual trees, parkland-style. An approach which tends to reflect human aesthetic values more than anything else, as we become increasingly aware that trees generally prefer to grow in communities; that there are often symbiotic relationships both in the soil and between different tree species which enable them to thrive; and that being planted out on their own can make trees more susceptible to stress factors like windblow. The advantage from a silvopasture system is that trees potentially use up less space planted this way; you can arrange them to your convenience; and spread their impact, such as shade, over a wider area, giving livestock a greater number of shelter spots to choose from (which in turn means that any animal muck is spread out over a wider area and not concentrated in a few select spots). In terms of fencing, this is probably the most expensive and time-consuming option, as you have to protect each tree individually.

- Trees planted in blocks. This makes them happy. They get to hang out with the friends and look after each other. It potentially makes the field challenging to negotiate with farm machinery, which tends to operate in nice straight rows. Fencing trees in groups is obviously more efficient then fencing them individually.

- Trees planted in rows. The traditional approach. If one thinks of hedges, the trees are in communities, and assuming your lines are straight they’re easy to navigate with farm machinery. They can be planted as wind buffers or on contours to manage water. If you plant in single species they can be easy to harvest or you can mix them up for diversity. They make for good wildlife corridors and fencing a single row of trees is a pretty straightforward undertaking.

Due to the prominence of the field in question at the entrance of the estate, it was felt by Dartington Hall, as the landlord of the farm, that aesthetics should be given some precedence in the decision-making for this field – and that rows or blocks of trees may have too solid an impact on the landscape.

Settling on a widely spaced parkland planting may also make it easier to observe browsing behaviours: which trees do cows eat; which do goats prefer; which trees do they consume more selectively; is there an association with an animal which is known to have a particular ailment browsing from a particular tree. That kind of thing. So we opted for a 27m grid planting of individual standing trees.

The reason for 27m spacing is because that leaves 1.5m on each side of the tree for the guarding and/or a buffer from farm machinery, and a row of 24m between each tree which can then be utilised by farm machinery operating on either a 2m, 3m, or 4m system (otherwise known here as ‘the Stephen Briggs approach’). The 27m spacing also give us the option to narrow the rows to 12m in future, as long as none of the guards are more than 2m wide, should we wish to increase the density of the planting.

Once we settled on a parkland-style planting, the main question then became how to protect each tree from livestock. Dartington Dairy has a herd of Jersey cows, which should respond well to standard tree protection measures but it also has a several hundred-strong herd of dairy goats. Some of the bigger goats have a reach of about 9ft and the herd has already had ample opportunity to demonstrate a complete disregard for fencing – or indeed any attempt to separate the goats from things they might like to eat.

How to protect the trees

As previously mentioned, the downside of parkland planting is that each tree has to be protected as an individual – so the next issue to address was how best to do this.

We have a ‘standard parkland tree guard approach’ already employed on the estate, but the current method takes up quite a lot of space, so we thought it might be time to consider something new. We were looking for a guard which was: cheap; easy to put up; economical on space; protective to tree roots; protective to the tree trunk; low on maintenance effort; able to prevent competitive grass growth at the base of the tree; able to survive being used as a scratching post by a bovine weighing in at around 1 tonne…

…and which could remain impervious in the face of a determined goat.

Collecting ideas from various places and people, this is the list of options we came up with as we mulled the challenge:

Option A

This was not on the list, this was on Ben Raskin’s twitter feed. Mostly we were just jealous at how easy this picture makes it look when you’re planting your trees in straight rows and aren’t dealing with goats.

Option B

A pretty standard approach to tree guarding which may protect trees from passing deer and rabbits, but is probably unlikely to withstand anything larger.

Option C

An option shared with us by Ella Sparks, one of our colleagues at Schumacher College, who has been looking at protecting trees from sheep. This single tall post with a circle of stock fencing and a rabbit guard is inexpensive and enables stock to graze right to the base of the tree whilst protecting the trunk but, as hilighted by her mentor Andi, of Fruit and Nut Ireland, there’s no support for the tree here and the single stake is unlikely to survive being rubbed on by sheep, let alone anything larger.

Option D

Either I took this at The Allerton Project, or I borrowed it from someone who did, or it’s from somewhere else but looks similar to Allerton’s. On our visit there we learnt that having two stakes at differing lengths seemed to give the guard greater stamina, and that having a narrow guard also enabled the sheep to browse off competing grass at the base of the tree without harming the tree itself. However, we were pretty sure these wouldn’t survive cows.

Option E

Another Allerton Project inspiration, again seemingly sheep proof but we didn’t think it would survive cows or goats. Obviously you could increase the height to offer the tree more protection but, given the incredible array of things the goats appear to find palatable we were pretty sure that the plastic netting wouldn’t survive for long.

Option F

This is the Protector Cactus guard and it came with a recommendation from Interlace Agroforestry that there was basically no animal it couldn’t survive. The only initial challenge being that it wasn’t available in the UK when we were doing our research.

Option G

An example of a classic estate guard, giving parkland trees long term protection, particularly around the roots due to the width of the guard – but they are probably the priciest option. We didn’t know if the horizontal bars might enable too much access to the tree or if it would simply enable stock to browse off the periferal leaves whilst leaving the central trunk of the tree intact.

Speaking to a couple of retailers the guard has been demonstrably succesful in protecting trees from deer, when used in conjunction with a plastic tube, and they felt it should be able to withstand goats. This guard also permits stock to graze some of the competing grass growth around the base.

Option H

Another option in metal, from Paddock Fencing, this time with more closely spaced vertical bars we thought might fare better against the determined mouths and reaching necks of the goats – but still with width for root protection and sufficient height, whilst enabling a little bit of browsing of any leaves which make it beyond the guard. Slightly less expensive an initial purchase then the other estate guard option but still more than any of the timber options.

Option I

A kind of ‘do it yourself’ version of option H but in timber, which brings down the cost. Our primary concern was: how do you maintain it? Its height makes it challeging to top up the mulch or replace the tree if your initial planting doesn’t survive – without taking the whole thing apart.

Option J

The ‘Mick special’, as devised by our local Woodland Trust Outreach Advisor. You probably can’t tell from the picture but under the plastic is a zigzag pattern of wire. As the guard angles out we thought if you increased the height it might stand a chance against cows and goats, having previously proven itself agianst sheep.

Option K

The status quo parkland tree guards currently used at Dartington. Inexpensive in terms of materials, they are effective against stock but they do take up a fair amount of space in the field. Their wide girth does a great job of protecting the tree’s roots but the downside is they require regular mulching to keep grass and weeds from competing with the tree.

Conclusion

As you can tell, each option has its pluses and minuses. In the end we decided not to select just one but to use this as an opportunity to experiment and trial a variety of guards in the field.

In my mind it’s a bit like Hunger Games but with goats – we’re sending the guards in pairs into the arena to see which survives.

Any chance of an update on how the different options have performed? I am looking at an agroforestry scheme similar to this but need to find an effective and cheap way to protect trees from grazing animals including cows and horses.

Hi Alasdair,

Glad you managed to get in contact with me via Harriet. I hope the Scottish Agro-forestry grant helps you get your project going. If you are still thinking of using Protector Cactus tree guards we could do with a chat about how you use them to make sure you are aware of how to avoid some of the issues. We are still finding our way with these guards but I think there are a few simple rules to follow that will give a trouble free result. As always doing the job right first time is going to be more economic.

Tim

Our single field trees are critical for many forms of wildlife and have been much under threat through loss and lack of replacement planting. Anything which encourages restoration of trees across the farmed landscape is timely and well worth seeking to get right. well done, crack on!

I suspect you guys of bias. That you’re the tree guard equivalent of those over enthusiastic parents who need to be kept away from the sidelines at school football matches.

very fair comment…cheering on our own!

That said we both really want to find cheap and effective solutions to allow far far more trees to be planted all across Europe, the World…and that needs a solution that is cheap an effective with livestock and wildlife grazing in the mix with trees. This could stop trees all being in hedges or woods and pasture and arable being treeless deserts.

We need to champion mass in-field tree planting to connect up our countryside.

From our own experience, if the rods are firmly fixed, the throny Cactus guards are unbeatable.

TESTIMONY En:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gNlNghL80Ws

Go Cactus guards! Thorny tridents will out-wit the goats!