In this immersive short reflection, Schumacher College lecturer Dr Sarah Elisa Kelly explores our understanding and experience of place and the language we use to describe our relationship with it. Sarah also includes a helpful exercise to start you on your own journey towards feeling more “place-full”. Enjoy!

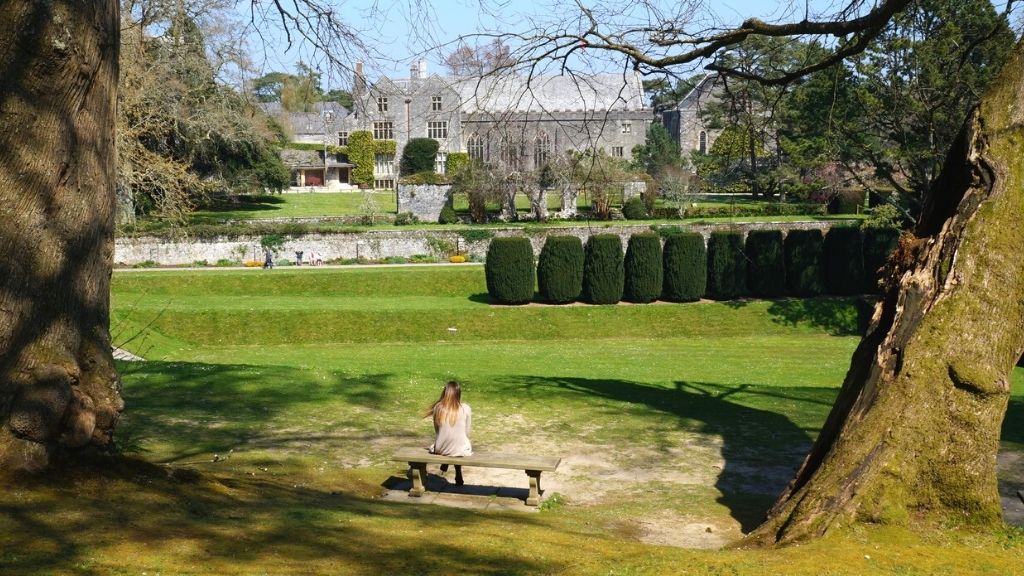

What is Place? This is one of the questions that is central to our explorations in the MA Engaged Ecology, and it is my hope that we will come to embrace many different possible answers. Recently, it has sparked for me a reflection on something I’ve been calling “place-fullness”. How might we enrich and empower our relationships with place through feeling ourselves more fully as place? My hunch is that one gateway might be through the lens of attention.

I’ve often heard it said that as humans we need to walk lighter upon the earth. Yet the very idea of walking “upon” is itself a misnomer. This is so much more than semantics; it is a question of orientation. While essential as an endeavour, I’m not so sure that lightening our step, our load upon the earth takes us far enough along the path toward radical change. Instead, we might need to make bolder paradigm shifts that require us to understand ourselves more comprehensively as already embedded and emplaced. From this position we might begin, however tentatively at first, to walk with the earth — not as a metaphor, but a genuine, experiential reality.

Inseparability, after all, is inextricable to living, it is the utter “is-ness” of being a being. It is the air, food, warmth, shelter that enables our survival. An intimate ecology, of which we are inescapably a part, is always the entanglement of a multitude of relations. We are all joined together, somehow, in a “we” that is often impossibly wide to comprehend.

Yet the experience of all this, is often much harder to grasp. Inseparability can feel physically, emotionally and psychologically elusive, even if intellectually we can come to understand the connection. In fact, using terms such as “connection” and “disconnection” can sometimes seem to unhelpfully reinforce things, making it sound as if the removal of our relationships was even a possibility.

There are many pathways we might take towards feeling ourselves more place-full. Some examples include becoming attuned to the weather and change in seasons, becoming knowledgeable of the names, patterns and pathways of creatures we co-habit with, learning the social, cultural and geographical histories of our given locations (particularly those histories whose visibility or lack of visibility advantages some while oppressing others). At their core, these are all forms of paying attention. We cultivate place-full relationships when we tend to them — when we give them our time, energy and effort.

Alongside this we can also practise orienting towards our basic “is-with-ness” by building greater capacity for such attention. Attention, as I choose to understand it, is a resource, something that can both dwindle and therefore be replenished. It is also a kind of muscle, something we can stretch, strengthen, and in doing so become more flexible in our use. In fact, the etymological root of the word attention is tendere (Latin) from the Proto Indo European ten meaning “to stretch”.

A useful exercise I’ve been experimenting with lately comes from the developing field of nervous system and trauma-based research (indebted to somatic practitioners including Moshe Feldenkrais, and more recently, Bonnie Bainbridge Cohen and Susannah Darling Khan). It involves learning how to “bridge” our attentions.

The intention is to explore layering the awareness of sensory experience, so that we can simultaneously feel ourselves internally, tend to external stimulus, and maintain a sensory connection to the interface, where self and world “touch”. It sounds complicated but is deceptively simple.

Try looking up now and paying close attention to the clock on your wall, really noticing its shape, colour, texture, how the light hits it, the sound it makes. Then after a while shift your attention to your breath, feeling the air rise and fall in the belly, noticing the rhythm, the length, differences in temperature between the inhale and exhale through your nostrils. See if this takes you somehow “away” from the clock, and explore how easy or challenging it is to return your attention but retain the feeling of the breath.

Now moving to another object, letting the eyes draw you toward something else around you that looks interesting, maybe a book or a plant (smaller and slower movements make the sensations easier to feel as you move your eyes, head and neck). Notice if you lose the feeling of the breath when you move. How is it to simultaneously feel yourself moving, feel yourself breathing and feel your attention “with” the world, attentive to detail such as the folds of fabric, the translucence of a leaf?

Next, layer in points of contact, where your body touches the floor beneath you, or the chair you sit on. Notice what your hands are touching, perhaps they rest on your legs or a wooden desk. Feel the quality of this interface, softness, scratchiness, hardness, warmth.

Stay with the sensations of contact and expand attention to the breath, then include the vision, sounds, smells if they are also present. There is no need to go looking for stimuli, you’ll notice there is a lot of variation already present, even on a seemingly blank ceiling (ironically many find this harder to practice outdoors at first, there is so much going on it can potentially feel overwhelming, so having a “container” can help while we adjust).

Many of us find it challenging to bridge sensations in this way, we can easily stay “in” or “out” but lose one strand of attention when we try to add another. Every so often though we might get glimpses of something. Perhaps it feels like the seams of life gently stretching, an uncanny blurring or the disturbance of seemingly solid boundaries. When this happens, the only way I know how to really describe it is a kind of shimmering fullness, an experiential embodiment of the aliveness of “place”. It encompasses me and more-than-me simultaneously, reducing neither to the other. The clock, the desk, the leaf, the sunlight, we become somehow reciprocal, with each other, deeply together.

Dr Sarah Elisa Kelly | Specialising in cultural theory and critical thinking, Sarah’s research questions how we think, speak and relate to the world as a whole. Sarah lecturers on the MA Engaged Ecology programme at Schumacher College, which is currently accepting applications for an April 2021 start.