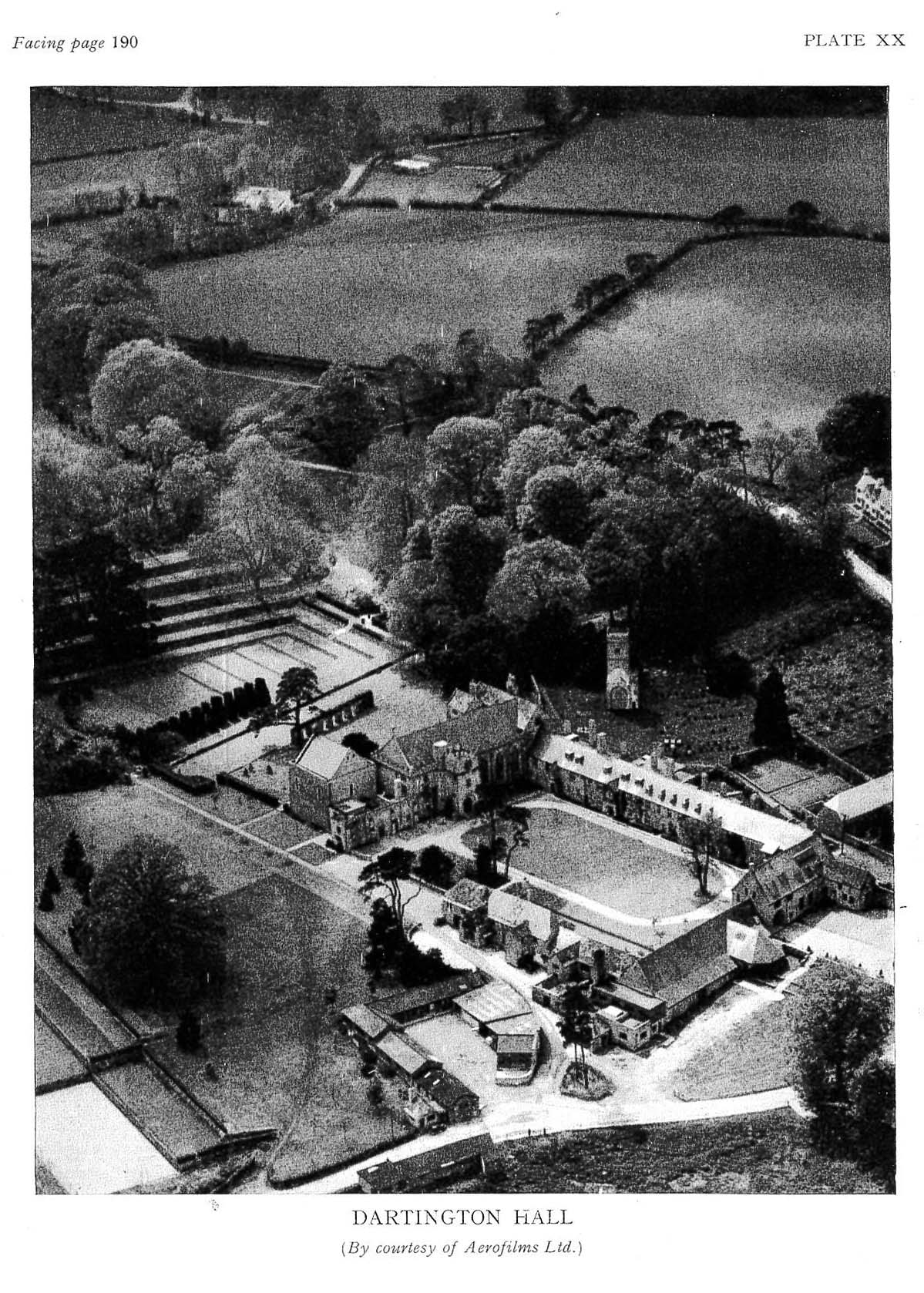

When you walk around the Dartington Gardens, do you have that ‘timeless’ feeling? The gardens sit well in the landscape, feel ‘natural’ and mature; it is hard not to believe this is how it has always been.

In fact, the current incarnation is a moving feast. In researching a Historical Report into the Gardens, I aimed to examine the process by which the gardens achieved their current configuration.

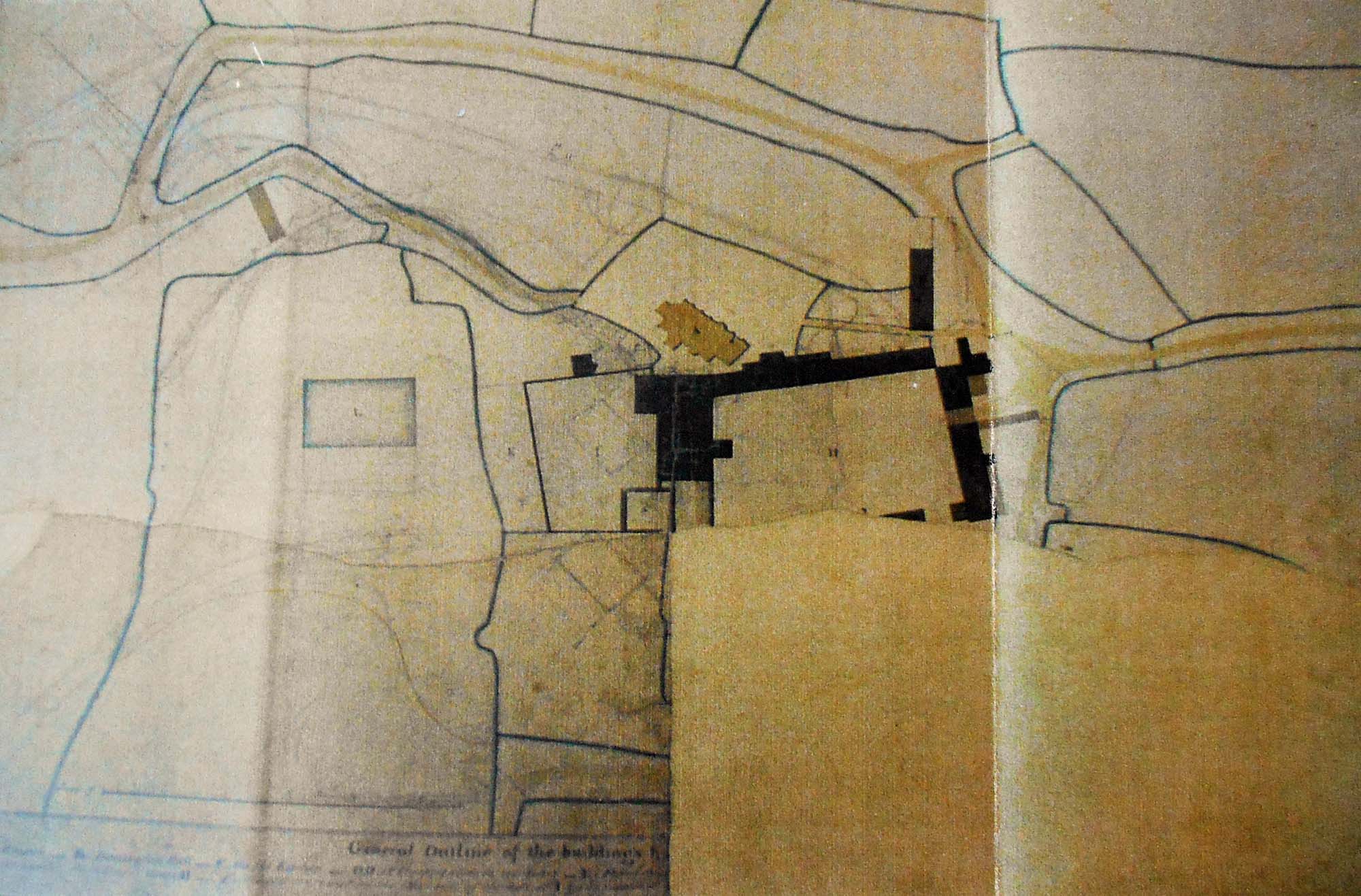

Collecting information about the gardens came from all directions, in particular Dartington’s archives. Now, there are two access points to the archives: a partial collection found online via the Dartington Online Archive Catalogue, or by visiting the full collection of physical archive papers that are located at the Devon Heritage Centre (Sowton Industrial Estate, Exeter). Most of my research took place in the latter – I spent many hours there, sifting through correspondence between Dorothy and Beatrix Farrand, or working through piles of Percy Cane’s proposed designs.

Visiting the archive is an interesting experience. On arrival, I would pass over my ID and put all valuables in a locker outside the archive room, only entering with a pencil (pens are banned) and laptop. After putting forward a request for the archive, there is a short wait while the archivist collects the document from one of the many back rooms. It is brought to your desk where you can then study, making sure you were in full view of the main desk, so presumably they can check you don’t turn the archive into an origami boat.

Having completed my research, I would like take you on a quick journey through time and give you an idea of just how much the Gardens have changed over the years.

Figure 1: This is an artist’s impression (made in 1957) of the Tiltyard in the 1300s, as a jousting area with terraces going up to the Hall. Picture shows the South Courtyard, which has now disappeared, except for the arches.

It was later concluded by Anthony Emery that this plan was never realised as, he argues, ‘it is extremely improbable that any wall would be allowed to terminate against the S.E. corner of the kitchen thereby increasing the liability of danger from fire’.

Figure 3: By 1845, the base of the Tiltyard was divided into two, a Dutch Garden (pictured) and Sunken Garden. Henry Champernowne is credited by his granddaughter in laying out a Dutch garden with the lower part as having “…corner beds with rhododendrons, azaleas etc…in the centre a monkey puzzle planted by his son Arthur at the age of 6”.

Figure 4: On 24 October 1930 the Dutch garden was removed by Dorothy Elmhirst and the level dropped. The profiles were sharpened, from ‘gently undulating slopes’, and work on creating the open air theatre commenced.

Figure 5: In 1954, the open air theatre was removed as the Devon climate was proved unsuitable. The base of the Tiltyard was made level and a gap opened in the Yew hedge for views down the valley. This picture shows piped Herringbone drainage being updated in 2009.

Figure 6: The Pinus radiata, leaning over the base of the Tiltyard, fell over in 2014, after a period of wet weather.

Do note that it is only by the 1840s that we have clear documentary evidence of a terraced garden: firstly in a photograph (Figure 3), and secondly on an 1889 OS map. Archaeologist Christopher Currie suggests that the Tiltyard terraces could have been installed in alignment of the newly planted Castanea sativa on the far side by 1682.

The question mark that hangs over this, and many other mysteries about the garden, can excite and frustrate generations to come.

Katy Ross (previously gardener at Dartington Hall)

Hi Katherine

I presume you’re in contact with garden Historian, Helena Gerrish – an expert on H. Avray Tipping?

I can put you in touch if not.

Fascinating! I’ve known Dartington since my first visit to the Summer School in 1970 and always loved the gardens so it’s very interesting to learn more about their history. Vicki