Mary Bartlett came to Dartington in 1963 as a horticultural student. After her training she became responsible for the glasshouses, nursery and walled garden.

Mary Bartlett came to Dartington in 1963 as a horticultural student. After her training she became responsible for the glasshouses, nursery and walled garden.

She is the author of several books, including the monograph Gentians, and Inky Rags, a review of which can be read here. She is now the tutor for bookbinding in the Crafted @ Dartington department. More blogs from Mary

Is the current postal system a mirror of society? Is there any hope for it?

In many ways the postal system is miraculous. Post from all over the globe will find its way to the right letterbox even when it’s wildly mis-addressed, thanks often to the local knowledge and enterprise of the postman.

Sadly, though, at least from the philatelist’s point of view, practice at sorting offices is going downhill. The occurrence of ruined stamps – scribbled over in biro or red felt-tipped pen is increasing, undermining postal values and relationships. Even ‘postage due’ stamps once had neat cancellations. All this behaviour is the cause of regular, bitter complaint in the philatelic press, as is the subject matter of new issues.

What might these issues, to mention a stamp term, have to do with Dartington and our interaction with each other and our local heritage?

Baghdad in British Occupation, The Story of the 1917 Provisional Stamps by Freddy Khalastchy, has lately taken me to a very dark corner in British colonial history. I collect British Military overprints, partly because, being a letterpress printer, I’m interested in the typefaces overprinters used. But the symbolism is fascinating, too, because overprinted stamps are lasting evidence of how one expansionist power pressed itself on another at a particular moment. Impression, oppression, suppression – all plain as day, on a ‘canvas’ less than one inch square.

Most people associate the First World War years with the battlefields in France; few have heard of the Mesopotamian Campaign. The Battle of Ctesiphon in November 1915; the terrible Siege of Kut between the December of that year and May 1916; or the forced march of prisoners north under Turkish guard. Overprinted stamps from the region and period are a potent reminder.

I think it was a very significant but largely overlooked influence on Dartington’s own history that Leonard Elmhirst was in Mesopotamia during those bloody years**. For what little insight we have into his experience, we must thank Paul Elmhirst, one of his nephews, whose privately published book The Family Budget preserves the correspondence between his family members during WWI. His brother Ernest, age 20, had been killed at Sulva Bay on the 11th of August 1915. William, age 24, was killed in France 13th November 1916.

Leonard, we learn, arrived in Basra in November 1916 as a YMCA volunteer from India, when in his early twenties. There are just a few photos from those years in the Dartington Archive. I’ve also managed to track down a copy of a pamphlet called The Land of Two Rivers that was published by the YMCA in 1917. Contaning notes on Mesopotamia and the Persian Gulf, it includes some dozen pages written by Leonard himself.

The detail is amazing and I wonder how he had managed to compile it. It also lists the battles up until May 1917 and some useful Arabic phrases. The book is a survivor, just as Leonard was himself. He was frequently ill and in hospital. But, as Michael Young observed in his book, The Elmhirsts of Dartington, he was even more tormented by religion than by the heat.

He wrote to his mother January 1917: “…the old creeds, formulas and doctrines no longer sum up my experience or satisfy my reason. They have not gone for good, and I think the fact dissatisfaction is not necessarily bad. It only means that when one has to work out a whole new philosophy of life, one tends often to be destructive at first rather than constructive”.

He stayed until August 1917 when he was invalided out, back to India.

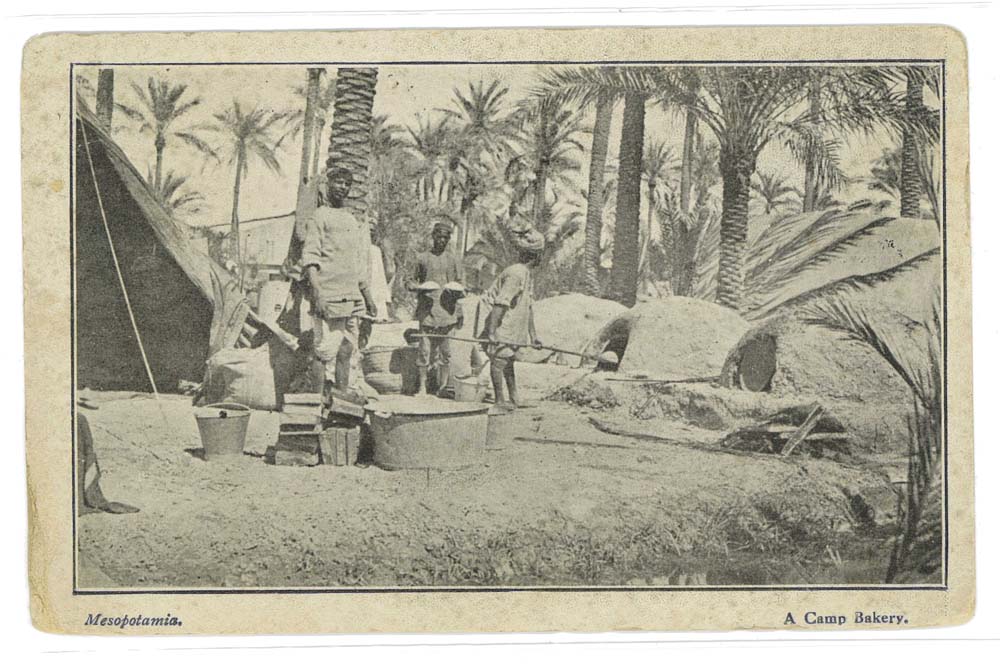

YMCA booklet (left) and photograph of a bakery in an Indian camp (right)

The importance of the postal system in terrible times of trench warfare is well documented in The Great War and Modern Memory by Paul Fussell. The Postal History of Iraq, Pearson and Proud tells a very different story. Piled up mailbags, no post for months, and severe censorship eventually led to General Sir Frederick Maude, conqueror of Baghdad in 1917, to complain forcefully.

I have a postcard from the Siege of Kut, a reminder that, for a time, postcards were all that a soldier was allowed to send home. In the 1980s you could visit safely and send home ‘wish you were here’ cards.

I once examined a collection of Iraq overprints and discovered that they had been sent home by their owner from a post office in Iraq at the time of issue – a century ago – as an investment. Such philatelic foresight!

Stamp collecting is a quest – sometimes quite thrilling, at other times – well, yes – rather nerdy. Recently at a local auction I lurked in a side corridor behind my friend Paddy Pollack (a specialist in second-hand medical books), to be able to bid unobserved for an album that had obviously been assembled with great love and care over a lifetime. I had to resort to cloak and dagger tactics to prevent it from falling into the hands of the dealers. They would have torn it apart to make the best profit from the contents. A massacre of a different type.

Say what you like about stamps, collectors and the stamp albums that still turn up in auction houses after their owners have caught the last post! – they have increasing rarity value. When I was a child, swapping stamps was part of school classroom life; the likelihood now is that we’ll soon be printing our own destination barcode labels and that will be that: no more stamps; no more stamp art. On a recent train journey through one of the country’s most spectacular geological landscapes, not one of the younger generation I saw in the carriages was looking out of the window. Everyone was plugged in and tuned out. Perhaps the course offered by Schumacher College – ‘Unplug, re-wild and reconnect’- could offer a solution. The Guardian that morning had the headline “Poorest to fare worst in age of automation”.

The connection with Mesopotamia? Tenuous – but I remember a great scholar of Middle Eastern history, Hugh Glencairn Balfour Paul CMG. He was British Ambassador to Iraq, Jordan and Tunisia, and his wife, Jenny, an indigo specialist, was part of the Dartington printmaking and bookbinding team who made A Printmakers Flora. Glencairn’s last line in his book Cicero: ‘Not to know what happened before you were born is to remain forever a child.’

2018 is a hundred years since the end of The War to end all Wars. At Christmas it will be 50 years since the death of Dorothy Elmhirst. We walk through her memory each day in the gardens. How do we contribute to the world we live? The stamps may not survive the sticky label or the army of alternative delivery systems but they will always tell a story if you are willing to take the time to look.

Mary

Footnotes

*Agatha Christie spent many years with her husband Max Mallowan, the archaeologist in Iraq. The Museum in Baghdad held many of the treasures until its destruction in 2003.

**The timing of this blog is apposite as two versions of Journey’s End, the hugely influential anti-war play by R.C. Sheriff, are coming to Dartington this spring – a play which owed its success to the financial backing and patronage of Leonard and Dorothy Elmhirst. The film adaption is screening at the Barn Cinema until 15 February, and a staging of the play by Dartington Playgoers runs from 20-24 March.

The experience Leonard had in Mesopotamia would have been very different to the scenes shown in Journey’s End but the trench warfare was just as horrific – with flooded trenches, searing heat, and plagues of various insects from lice to sand flies. Many soldiers queried the term ‘Garden of Eden’ and pondered what hell would be like. The belief in funding Journey’s End was a possible response to help atone for the suffering, loss, sadness and to find another way.

The first-hand accounts are grim; recently I read an annotated copy of A Study of the Strategy and Tactics of the Mesopotamia Campaign by A Kearsey 1917, very informative and sets out the failings.

This is fascinating, Mary. Hurrah for philately, and people who can read the depths of history from tiny pieces of inky paper. Did you know T.E. Lawrence helped design some stamps for Hejaz?

My grandfather was there in Mesopotamia; I don’t know much but somewhere in Dad’s attic is a box of yellowing photos and I remember seeing a crowd of tommies in front of the arch at Ctesiphon. Later on he was torpedoed near Crete; now you can watch YouTube videos of holidaymakers scuba-diving around the wreck. How times change.

Dear Alan, thanks for this. I will have to look up the stamps by Lawrence, yet another quest.

Think you will have to find the box in the attic as Ctesiphon such an important historical place.

I was lucky enough to go to a conference on Nineveh in the British Museum with the American John Malcolm Russell, author of The Final Sack of Nineveh many more books and articles. He was in Iraq with the US forces and sent me some amazing pictures of the arch.

The postal history is always the key to the history and I could spend so much more of my time on it if there weren’t so many other jobs to do.

Apparently Blair loved acting and the reason being because he enormously enjoyed pretending to be someone else. As a young man he performed in a production of A Journey’s End, and its inception and writing as you have informed me, Mary in your fascinating blog ,was financed by Leonard Elmhirst. I have read that, from his experiences in this play, in which he portrayed a leading character appalled by the niceties of war, Blair gained a philosophy of ‘in for a penny, in for a pound

Dear Ros, The play was funded by Dorothy who then used much of the money made from the success of the Savoy performance to rebuild what is now the Barn Cinema. I guess you are referring to The Accidental American by James Naughtie which has the front cover of Tony Blair, depicting him on a dollar bill. In 2003 I did a book called Land at Sutton Close, a comment on the war, which looked at ancient Assyria, the current planning system in Torbay and the connection with Agatha Christie and her husband Max Mallowan and his excavations in Iraq.

I keep plodding through as much as I can written about that war in Mesopotamia.

You may be interested to know that one of Leonard’s younger brothers, Vic, found himself in the army in Mesopotamia in 1919 when, as a second Lieutenant, he was sent with his platoon (mounted on camels) to patrol the desert interior with instructions to ‘find out what the damned Bolsheviks are up to’.

There has been much written about the aftermath of the initial campaign. Empires of Sand, Walter Reid is a comprehensive account.

Modern writers include Illan Pappe, who lived on the estate for a while, and is now at Exeter University. Eden to Armageddon, Roger Ford, Britain in Iraq, Peter Slugget, Understanding Iraq, William Polk.

The problems continue on a daily basis.

Thank you so much for sharing, Mary. I remember reading Journey’s End for GCSE English. When I was in New York for the holidays, to my delight I walked by a theatre off-Broadway where it was showing… so I dragged my parents. We were reading the program when I noticed a sentence which said that the play was supported by the Elmhirsts. Somebody is watching from up there! Best wishes!

Thanks for the comment. Leonard’s time in Mesopotamia has never really been written about.

He would have known the suffering the Indian troops went through both at Kut and the forced march afterwards. Maybe that was why he always had a deep interest in India.

An interesting article that highlights Leonard Elmhirst’s notes on Mesopotamia in the Great War. Mesopotamia has always been a political melting pot. Although in 1922 Churchill together with T.E. Lawrence was reputed to have devised a political solution that satisfied all the key political influencers at that time. After Mesopotamia Churchill then concerned himself with the Irish civil war, which considered to be much more of a challenge!!!

Many thanks for the additional information. Letters of T.E Lawrence, edited by David Garnett page 124 and Seven Pillars of Wisdom. T. E. Lawrence, new edition 1940, page 283 footnote. Lawrence had tried to negotiate with the Turks the release of the prisoners from Kut with no success.

Lawrence visited Dartington, one can only imagine what he and Leonard talked about.

I often wonder what T.E.’s thoughts must have been on visiting Dartington. By the time he visited, he had largely disassociated himself from his activities in the Middle East, and probably would have found it abhorrent to talk about. One can imagine any conversation beginning with the Brough Superior motorbike on which he undoubtedly arrived – an obvious and safe subject.

Then might T.E. mention that his younger brother Will had known Rabindranath Tagore in India in the years before the war? Will had spent a year and a half teaching at St Stephen’s College in Delhi, where his colleagues had included Tagore’s great friend, C.F. Andrews. Will himself had spent Christman 1913 at Santiniketan, a visit which made a tremendous impression on him, as evidenced in his letters. In 1915, Will had returned to fight in the war, being killed in only his first week in France .(He was officially “missing in action” for six months, and T.E. would have got his father’s letter confirming his death on his return from Kut.)

Might T.E. then have mentioned to Leonard how he, too, had met Tagore in 1920, first in William Rothenstein’s studio in London, then for tea in Oxford. Both were by now disillusioned men – Tagore over the massacre at Jallianwallah Barg and T.E. over British betrayals in the Middle East – yet Tagore had liked T.E. “very much”.

And there was another family connection that might have come up in the conversation. On his way out to India in 1921, Leonard had written to Dorothy how T.E.’s elder brother Bob was to join him as a cabin-mate from Port Said. (Bob was going out to China as a medical missionary.) Sadly, there’s nothing more in Leonard’s letters about this. But might he have had some reminiscences from their voyage to relate?

But I imagine most of T.E.’s thoughts must have been on the hall. Enthused with the ideals of medievalism, as a young man he had dreamed of building his own medieval-style hall as a base for printing fine books. It must have been fascinating for him to see the hall being renovated in the same Morris traditionsthat he so loved. But might there have been bittersweet thoughts too?

T.E.’s real surname was Chapman. By now he knew the truth of his parents’ adulterous relationship and his own illegitimacy. There is evidence of him trying to trace his father’s Anglo-Irish background, so did he come to Dartington in the awareness of his possible relationship to the Champernownes? Had he seen the memorials to the Champernownes in the old church tower, might he have wondered if all this might have been his, had family circumstances been different? (There’s much more of this in Ronald Knight’s book, T.E. Lawrence’s Irish Ancestry and Relationship to Sir Walter Raleigh.)

Well, it’s all speculation, Mary, but I hope these suggestions will be of interest to anyone who’s ever pondered the connection with T.E..

Another great blog post. Love the phrase: ‘Such philatelic foresight!’, I’m wondering where the stress should be in that middle word.

Really interesting about Leonard’s war experiences. Thanks Mary.

It was a lot of research through the winter but an amazing journey. Thanks for the information on the song ‘And the band played Waltzing Matilda’ by Eric Bogle about the suffering of the Australians in another part of the war. I have also found Kipling wrote a poem ‘Mesopotamia’. Today one of my class came in with a collection of old photos of Iraq. A never ending journey as has been said before.

It is telling that Leonard walked alone in the Hall Gardens for two hours on a cold December night after hearing his first reading of Journey’s End. When he returned he and Dorothy told Maurice Browne that they would support a West End Production of the play.

I am sure that Leonard saw and heard his brother William (who had been killed on the Somme) in the moving scenes of the play and that the play expressed the feelings of grief which Leonard (and his other brothers) had been unable to express immediately following the death of his eldest brother and boyhood hero in 1917.

Leonard certainly had concern for mankind’s suffering, but I think that with Journeys End it was deeply personal.

Dear Paul, thank you for the comment.

The more I have read and researched it must have been a terrible time. His time in Mesopotamia would have only reinforced the sadness for all those who suffered unimaginable conditions with little hope of survival. The conditions the British and Indian troops suffered on the forced march north he would have known about. Journey’s End, as you say must have been deeply personal.